JUSTICE INFO. The situation seems more than critical: the States Parties to the International Criminal Court (ICC) do not seem to be able to appoint the new Prosecutor as planned in December. Yet in June, a selection committee had chosen four candidates for the post, none of whom reached consensus. How did we get there?

PATRYK LABUDA. The idea was that states would appoint a candidate to be the next prosecutor by the 22nd of October, but we recently found out that the nomination period had been extended until the 22nd of November. Yesterday we found out that the entire election process has been thrown into flux with the Assembly’s decision to expand the list of candidates. This is a major development and it is hard to know what will happen. Initially, the expectation was that one of four shortlisted candidates would be nominated, but behind the scenes there has been a struggle between states who want to nominate one of those 4 candidates and states who wanted to open up the selection process and include people who had been on the initial long list of 14 candidates. We now know that the second group of states has prevailed.

It looks increasingly likely that no candidate will be nominated at the Assembly of the States Parties (ASP) that is meeting in early December. Ideally, States wanted to elect the prosecutor by consensus. Increasingly, it looks like this may not be possible. This would be the first time in the ICC’s history that States are unable to reach consensus by a self-imposed deadline. Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda is required to step down in June 2021 and normally what happens is that states appoint a successor at the annual ASP meeting of the preceding year. Now it looks like, for the first time, potentially no candidate will be nominated and we will have to wait longer for a final decision on the next Prosecutor.

A year ago, when the whole selection process was put in place, a committee on the election of the Prosecutor was created to avoid political bickering among states. That, unfortunately, has not worked. On the contrary it seems that this new selection process has made things even more complicated. I think that paradoxically, what may have happened is that by putting in place a more formalized process states have politicized the election even more.

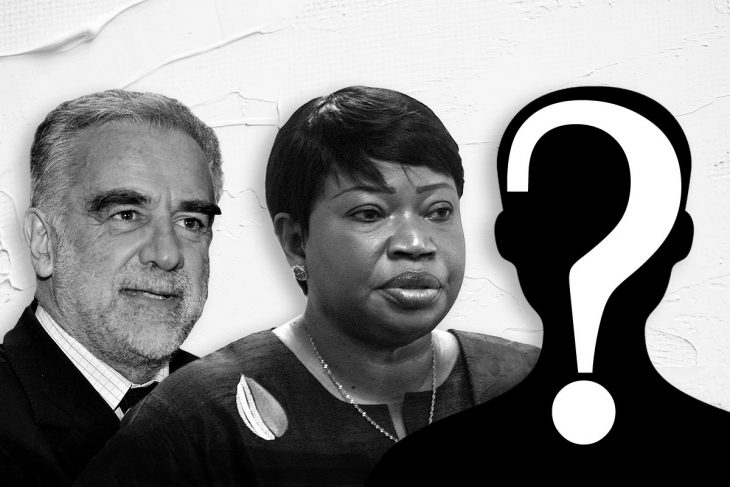

The first two ICC prosecutors, Argentina's Luis Moreno Ocampo and Gambia's Fatou Bensouda, have for different reasons failed to command full respect on the international scene. Isn't the stakes of the election of the third prosecutor particularly high this year for the future of the ICC?

The stakes are high for this election. Who the next prosecutor is will determine the court’s future, and I don’t think it’s alarmist to suggest that the court’s future hangs in the balance. As we know, the United States has mounted a concerted campaign to undermine the office of the prosecutor in a really unprecedented way, and the question of whether the next prosecutor will succumb to this kind of political pressure is acute. I think there is a fear among States that if the wrong person replaces Fatou Bensouda the court and especially the office of the prosecutor may lose relevance or worse.

That might explain why the election has become so politicized. Add to that the fact that the shortlist that was produced by the committee did not meet everyone’s expectations. First of all, many States feel that, among the 4, the Irish candidate was given an unfair advantage, for a variety of reasons including the ‘rotation principle’ in international relations, which means that the two African candidates are not being seriously considered by states this time around. It would be a diplomatic ‘faux pas’ to choose an African after the current prosecutor, who is from Gambia. So, some States feel they haven’t really been given a choice. At the same time, some States are unhappy with the fact that people who are supposedly on the soon to be made public ‘long list’ did not make the cut – such as Belgian Serge Brammertz, the current prosecutor of the Mechanism for International Criminal Tribunals, or British Barrister Karim Khan, head of the Iraq mechanism, both rumored to be among the favorites and considered to be very skilled practitioners with a lot of experience. In that regard, the second objection of States seems to be that the wrong people were shortlisted.

Then, there are some perceived weaknesses of the first and second prosecutors that States presumably want to avoid. States would not want to choose somebody who is not very good at managing diplomacy. Luis Moreno Ocampo was considered a very vocal prosecutor. Some States would certainly prefer a prosecutor who is more adept at managing investigations and getting that part of the job right rather than focusing on the public dimension of the office of the prosecutor’s work. The next prosecutor has to have political gravitas, has to be somebody who is respected, who is able to negotiate with powerful state actors. With respect to Fatou Bensouda, one serious concern that she hasn’t been able to allay during her nine year mandate, is the quality of investigations. Many cases collapsed on her watch.

States will be attentive to the next prosecutor’s ability to collect evidence that withstands scrutiny in a court of law. Whoever is chosen must not only be a good diplomat, but also be able to manage a team of investigators who can put together a solid case that then leads to convictions. Too many cases collapsed in the last few years, against the Kenyan president, against the former Democratic Republic of Congo vice-president, and most recently against the former president of the Ivory Coast. States want to make sure that whoever is chosen is able to prosecute cases that will not fall apart at trial. I think those candidates do exist but then, as we know, there are other reasons why this election is so controversial…

Do you refer to the #MeToo suspicions that a number of NGO’s have warned about, including Open Society Justice Initiative again last week, in a letter addressing “Grave concerns about the ICC Prosecutor Election and the urgent need for vetting”?

What we do know is that the moral standing of candidates has played a major role in the selection. The prosecutor has to be ‘a person of high moral character’, according to article 42 of the Rome Statute. From the start, NGOs have been pushing hard to incorporate some form of vetting that would allow States to ascertain whether candidates are accused of sexual misconduct. And from the beginning, there has been a suspicion that there are concerns regarding people who are running for this position, although it is important to note that no allegation against specific individuals has been made publicly.

After yesterday’s decision to expand the pool of candidates, the question becomes: if States do not want to choose one of the four candidates on the short-list and, at the same time, they cannot choose those rumored to be involved in sexual misconduct, is there any way out of this impasse? Only States involved in the selection process can tell us for sure what is preventing them from choosing a candidate, but there is certainly a perception among Court observers, who are external to the process itself, like myself, that this issue of ‘moral character’ is causing much greater problems this time than in the previous election nine years ago. It seems clear that this issue is influencing the election. I think we’ve reached a sort of impasse, not just because of potentially what States are doing behind the scenes, but also because the selection process that was established last year did not have the formal authority to resolve these issues. The committee on the election of the prosecutor did not have a mandate to make determinations on the validity of allegations of sexual misconduct. If there is no process to ensure that they are addressed in a satisfactory manner, this is a real ‘catch 22’ for states, who cannot just ignore such allegations either.