These documents were never meant to be seen by anyone outside the Syrian regime. “Highly confidential” is written at the top of two perforated A4 sheets that are densely covered with Arabic writing. An unremarkable official letter at first sight, they represent a turning point in the conflict between the protesters in Syria and the Assad regime, that had just started at the time. “The time of tolerance and meeting demands is over”, states the circular by the Central Crisis Management Cell (CCMC) to the heads of the secret service branches dated 18th of April 2011. Another written instruction follows two days later: to commence a new phase in which the protesters should be met with force.

Digital copies of the two documents were projected onto the courtroom wall last week in Koblenz, Germany, where two former secret service members from Syria have been on trial since April. The documents were presented by Christopher Engels, director for investigations and operations at the Commission for International Justice and Accountability (CIJA) who testified as a witness and expert on November 17-18. In a 63-page PowerPoint presentation he showed the judges further documents that his organisation has collected since 2012. They may be able to prove, among other things, that the 4000 cases of torture and 58 killings main defendant Anwar Raslan is charged with, amount to crimes against humanity.

“When spotted, kindly arrest them”

The CIJA is an international non-governmental organisation (NGO) that has been gathering documents in Syria and taking them out of the country, in order to secure them for future criminal investigations. Their work is financed by those countries whose law enforcement agencies wish to use the gathered material: currently these are Germany, Canada, the US, the UK and the Netherlands. “We started this work after observing a gap in international criminal investigations in the past”, explained Engels who like most of his colleagues has many years of experience as an investigator and consultant in conflict and post-conflict areas such as Afghanistan, South-East Asia or the Balkans. The most important evidence often disappears during the conflict, said Engels. “It is destroyed, gets lost or is hidden by individuals who know that it could harm them.” In the case of Syria, the CIJA claims to have beaten the Assad regime to it. Since 2012, the organisation has collected 800.000 pages of Syrian government documents as well as 469.000 videos or other digital files. All of them are stored in an undisclosed location.

In court, Engels used some of these documents to retrace the hierarchical structure of the Syrian regime and its security forces. His conclusion: The orders came from the very top. In August 2011, the CCMC, the highest ranking state body created specifically for dealing with the uprising, sent a letter to the heads of the security branches, ordering them to arrest “those that finance demonstrations, those that incite demonstrations, those who are members of opposition coordination committees, those who are communicating with people abroad and those who are speaking with foreign media.” The same order was found again word-for-word in documents that were later sent to the local secret service units. And finally, it reappeared in individual interrogation protocols. Engels showed the court a protocol from the CIJA archive, where an inmate is asked to provide names of “those that incite demonstrations, those who are members of opposition coordination committees.” Based on all the testimonies witnesses have given in Koblenz until now, the inmate’s answer was most probably extracted under torture. According to the document, the twelve names he provided were circulated. They appear again in a list sent by the military intelligence to the military commanders with the instruction: “When spotted, kindly arrest them and bring them to us.”

When the regime leaves, documents are left behind

From the very beginning, a crucial part of the CIJA’s work has been to document the exact provenance of every collected page. “That was the basis for our concept: that we attempt to collect evidence and preserve it in a way that it would still be usable twenty years later”, said Engels.

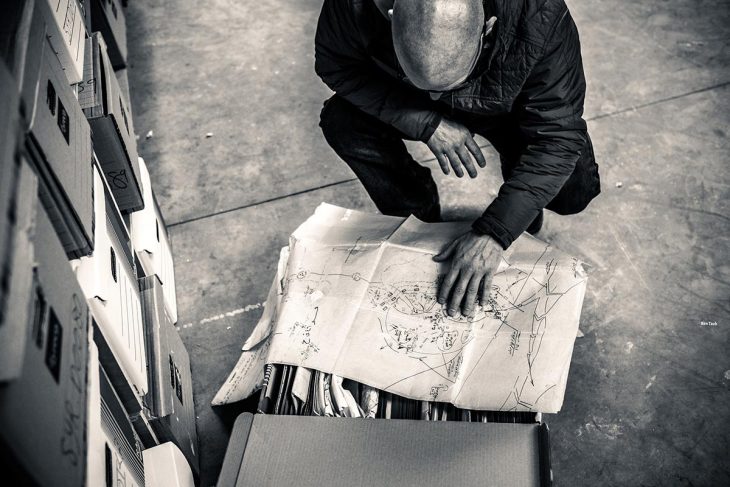

Engels is probably aware that his organisation has been criticised in the past for conducting investigative work which is usually done by international bodies like the United Nations or the International Criminal Court. There have been concerns that a private organisation might not investigate impartially, or that its methods would not produce reliable evidence that could stand in a court of law. To ensure the evidential value of the presented material, Engels provided the route that each document took from Syria through Turkey to the CIJA headquarters. Most of the documents were collected by CIJA staff on the ground between 2012 and 2013. The examples Engels showed in court were found in Idlib, Raqqah and Deir az-Zor. “We do not collect material from behind conflict lines”, said Engels, stressing that the CIJA only cooperated with defectors, not people currently working for the regime. “Only when one conflict party is pushed out of an area, then our colleagues go in and collect all the documents left behind in government offices and buildings.”

At that point, the organization’s investigators do not look at the material or sort it. Their only job is to get it to a safe location in Syria, where it can remain until an opportunity arises to transport it out of the country and to CIJA headquarters, usually via Turkey. “Depending on the circumstances, this can take from a few days to a year”, Engels explained. The next step is to scan all the pages separately and archive the physical material. Only then does the staff begin sorting through the digital copies, assembling pages that belong together and analysing their contents. In order to corroborate the information found on paper, the CIJA interviews witnesses such as former detainees or regime members. Altogether, they have spoken to 2,500 witnesses. Seven of them identified the defendant Anwar Raslan as head of investigations at branch 251, or Al-Khatib branch, in Damascus.

Two documents with Raslan’s signature

Before the German federal prosecutor began investigating Anwar Raslan, it had already been called to the CIJA’s attention that the Syrian ex-colonel was residing in Europe. Under the codename “Czech” CIJA staff started building a dossier on him. In April 2018, the German Federal Police (BKA) requested information from the CIJA on Raslan, which they received. Part of the dossier are two investigation reports with Raslan’s signature on them, and a third one with his name on it, but no signature. Regarding clues that Raslan was directly involved in abuse, Engels stated: “We found the evidence that Mr Raslan was in charge of the investigation branches in 251 and 285. These branches were in charge for the interrogation of detainees. Detainees were abused during interrogations in those branches.“ When asked whether from this he deduced that Raslan was responsible for abuse, Engels said yes.

Engels’ testimony and the CIJA documents are not only important with regard to the role of the defendant, but also for understanding the framework that he was acting in as head of investigations in a secret service branch in 2011 and 2012. All of the CIJA’s findings suggest that the abuse of prisoners took place in a widespread manner, all over Syria, Engels told the judges in Koblenz, while presenting a map showing the movements of detainees from regional branches to the capital and back. “And they were systematic, in that it was the same type of abuse across different offices, with the same purpose to find information”, he added. A widespread or systematic attack on a civilian population – that is the definition of crimes against humanity according to the Code of Crimes against International Law.