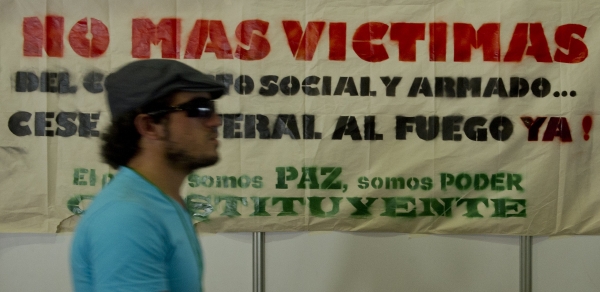

Peace negotiations are currently taking place in Havana between the Colombian government and the FARC (the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) to end the oldest internal armed conflict in the world, with more than 6 million victims since 1964. As in many other transitional situations, Colombia is already facing various facets of what one may call the ‘justice dilemma.’ Should the crimes committed during the conflict be at least partially amnestied for the sake of peace or should prosecutions be actively pursued? Can the government seek to achieve the same form and degree of accountability for all parties in the conflict? Will this not be impeded by the fact that the FARC is currently sitting at the negotiation table? How might the other parties react if the FARC seems to obtain preferential treatment? The answers to these questions could either undermine or enhance the possibility of peace in the country.

The conflict in Colombia

The 50-year armed conflict in Colombia involves various armed parties: guerrilla groups (particularly the FARC and the ELN – the National Liberation Army), paramilitary groups and governmental military forces. The Colombian conflict is not only fought in the battlefield. Political parties, political leaders, corporations, landowners and the like are also involved in various ways as evidenced by the Para-politica scandal where some politicians, including members of Congress, were found to be involved with the paramilitary.

The causes of the conflict have varied historically. Guerrilla groups were initially formed to resist capitalism, land dispossession, poverty and inequality. Paramilitary groups were formed, among other hypotheses, as a self-defence mechanism against the guerrillas, and their existence was legitimised by governmental decrees. These original causes have changed over time and other important factors such as drug trafficking and land control have fuelled the conflict, obscuring the initial ideological motivations.

The conflict has produced million victims. According to the report by the National Centre of Historical Memory “¡Basta Ya!” more than 220,000 people have been killed, approximately 5,700,000 million have been internally displaced, around 25,000 have been subjected to enforced disappearance and more than 30,000 have been kidnapped.

Various peace processes have taken place in Colombia during these years of conflict but they have not yielded peace. The only major achievements have been the demobilisation of some guerrilla groups such as the M-19 and the EPL in 1990 and the demobilisation of paramilitary groups from 2002 onwards. Attempts to achieve peace between the FARC and the government have failed. Nevertheless, peace negotiations started again in 2012, with a six-point agenda: 1) an agrarian development policy; 2) political participation of the opposition and new political movements resulting from the peace agreement as well as of all sectors of society including vulnerable groups; 3) an end to the conflict; 4) curbing drug trafficking; 5) victims’ rights including reparation and truth; and 6) the implementation of the peace agreement. By May 2015, the Government and the FARC had reached partial agreements in relation to the agrarian policy, political participation and drug trafficking. The peace talks continue in Havana. The point on victims’ participation is currently under discussion, and victims’ delegations have travelled to Cuba to actively participate in the talks. Talks are also taking place about the end of the conflict. This is the closest that Colombia has been to signing a peace agreement with the FARC. The process enjoys massive international and national support, and it was a decisive issue during the campaign for the past presidential elections, which resulted in the victory of President Santos for a second term.

The justice dilemma

Impunity has reigned in Colombia during these decades of armed conflict, as illustrated in Morris and Lozano’s documentary “Impunity”. However, international law, a strong civil society and the pressure of the international community are pushing the country towards accountability. They claim that international crimes have to be investigated and its perpetrators prosecuted and punished. Some victims support their call. However, bringing perpetrators to justice is a more than challenging task and Colombia faces an important justice dilemma: what to do with the crimes committed with the FARC? This is currently part of the peace talks. Nevertheless, the justice dilemma goes beyond the FARC as the conflict, and its many crimes, has been possible thanks to a variety of actors (including but not limited to members of the military forces and financial and intellectual actors) all of whom should also face the question of what to do with their crimes in a country that claims peace.

a) Negotiating justice with the FARC

One of the key issues at stake in the peace negotiations is the price the FARC is ready to pay in terms of justice to achieve peace. It is clear that the FARC is not going to demobilise and arrive at a peace agreement if the cost is imprisonment for what they consider to be a justified fight against the establishment, while they also forfeit all financial benefits from the conflict (territorial control, drug trafficking, extortion, etc). President Santos knows this and, in order to facilitate peace negotiations, he convinced Congress to approve the Legal Framework for Peace (Marco Jurídico para la Paz) which establishes principles to select cases to be investigated. For instance, the Framework establishes that the Government through a statutory law can determine the criteria to investigate only those that bear most responsibility for the most atrocious crime, while those who committed less serious crimes could benefit from a suspension of a penalty or alternative sanctions. The selection of cases is, however, controversial even though it is well known that in a conflict with millions of victims like the Colombian one, it is factually impossible to prosecute all perpetrators.

The FARC opposes the Legal Framework for Peace, viewing it as a unilateral decision by Santos rather than the result of dialogue. Furthermore, according to a press release from December 2014, the FARC claims that the crimes they have committed fall within the framework of the political crime known as rebellion, which opens the door for an eventual amnesty. Therefore, part of the justice dilemma is whether peace negotiators in Havana will reach an agreement on a blanket amnesty under the ‘political crime’ argument or whether they will opt for some type of different arrangement such as the one established by the Justice and Peace Law which the Legal Framework for Peace would also support.

A blanket amnesty could have serious legal and political consequences. Legally speaking, it would contravene various regional and international norms that bind Colombia and it would generate legal insecurity for those who wished to be protected by it, such as a possible intervention by the International Criminal Court. It is possible that such an amnesty may be considered illegal under international law as has been declared by the Inter-American Court in relation to Peru, Chile or Brazil to name a few or domestic law as the Argentinian case illustrates. Politically speaking, it could fuel conflict and prevent reconciliation as victims, former paramilitary members, the military and important sectors of civil society would not easily accept it.

An exceptional mechanism, judicial or non-judicial, limited to the investigation or prosecution of a few guerrilla members with reduced punishment or alternative forms of punishment would be preferable legally and politically. However, it must be carefully crafted so as not to be in breach of international law and to avoid upsetting victims and other key actors in society.

President Santos, who was re-elected in June 2014, appears to be aware of this, and in order to prevent an agreement that could be politically and legally dangerous, he is addressing this dilemma by obtaining democratic approval for the final peace agreement in Havana. He seems supportive of a referendum to validate the agreement and recently approved Law 1745 of 26 December 2014 on the requirements for such a referendum. The FARC, however, has rejected the idea of a referendum, stating that a national constitutional assembly is the way to get validation of the peace agreement and provides the opportunity for a new social contract as a new Political Constitution would be agreed.

But the justice dilemma, as already noted, is not only about the FARC. It has other fronts that sometimes go unnoticed such as the justice deal with the paramilitary groups and members of the military and the balancing exercise that justice calls for when dealing with the serious crimes of the three armed groups in the conflict.

b) The justice and peace law as a limit to the negotiations

Discussions about justice with the FARC are happening while the Justice and Peace Law is implemented. This Law was adopted in 2005, envisaging a plea bargain according to which demobilised members of the paramilitary groups or the guerrillas must confess all of their crimes to benefit from an alternative sentence of 5 to 8 years in prison. Under this Law, more than 50,000 members of armed groups, primarily paramilitary groups, have demobilised in the country. Of this number, approximately 4,500 have been indicted under the Justice and Peace Law. Only 1,800 are in prison and some of them have already served up to 8 years in detention without being condemned. They are asking to be released. In almost a decade of implementation of this law, only 26 judgments of first instance and 13 judgments of second instance have been completed.

This Law and its impact on the lives of those demobilised limit the current negotiations with the FARC. The FARC cannot get a deal that is seen by members of the paramilitary as more lenient than the one they got. Therefore, any agreement with the FARC must include similar principles to those applied under the Justice and Peace Law.

c) The deal with the military forces

The crimes committed by the military are meant to be investigated and prosecuted by the ordinary criminal justice system when the crimes at stake are not related to the military service (such as disappearances) and by the military criminal jurisdiction for other crimes (such as disobedience). However, few members of the military have been prosecuted and sentenced in Colombia. For example, of the more than 4,000 killings of civilians (as if they were guerrilla members) committed by members of the military to obtain a promotion or other reward, known as “false positives”, those who have been punished are often low rank soldiers but not high ranking members of the military. This raises an important question regarding the handling of these serious crimes by the military. The answer given by the Government and Congress has been to expand the scope of the jurisdiction of military courts. Indeed they tried to adopt a constitutional amendment that raised serious legal concerns and was declared unconstitutional by the Constitutional Court. The legal reform of this jurisdiction continues in Congress. This means that the military is also trying to strike a favourable deal in relation to their serious crimes and that this should be duly taken into account while negotiating with the FARC.

Coping with the dilemma

What lies before Colombia is a serious justice dilemma. Will the peace process result in the establishment of different judicial and non-judicial mechanisms to deal with the crimes of the various parties to the conflict? If that is the chosen approach, how would the government justify a differential treatment of the different armed actors so as to be in line with constitutional and international law? What are the minimum standards of justice required to fulfil the rights of victims and to comply with international law? Would such an approach yield the peace that has been sought for so many years?

Addressing the various dimensions of the justice dilemma requires creative thinking and a balancing exercise: for example, it might be necessary to envision forms of punishment other than imprisonment, but without forgetting that victims have rights that should be protected during any peace negotiation. Alternative forms of punishment are needed in conjunction with imprisonment or replacing it.

A balancing exercise is also needed as it is legally and morally essential to have a proportional approach to the crimes of all parties to the conflict: guerrillas, paramilitaries and members of the military. This does not mean that all of them should be treated equally. It is legally possible and even desirable to treat the various armed parties differently by applying different forms of accountability. Nevertheless, any distinction in treatment should be reasonable and clearly justified.

Finally, the responsibility of powerful actors, such as politicians, landowners or corporations should not be forgotten. They have fuelled the conflict all of these years. Facing the justice dilemma also requires dealing with their crimes. This is the part of the justice dilemma that has been avoided and which needs to be addressed to partly fulfil an important pillar of transitional justice: guarantees of non-repetition.