“There is no way the president on his own could have had the power to turn the Gambia from what it was, to being an Islamic State,” said Gaye Sowe, still chocked, before the Gambia Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission (TRRC) on April 1. The former magistrate and constitutional lawyer was one of the five legal experts called to dissect, last week in Banjul, how Yahya Jammeh weaponized the legal system in the small West African country.

That was in December 2015, when Gambia’s President Jammeh suddenly declared his country an “Islamic State”, with no changes to the laws and in the Constitution. A news that was particularly disturbing for most of the population. “That was very unconstitutional”, said Sowe.

Ten years earlier, however, the Constitution had been one of the firsts steps in Jammeh's takeover, Sowe described. Jammeh’s military takeover, in July 1994, was reportedly aimed at ending self-perpetuating rule and corruption. Immediately after, the “military council” headed by Jammeh and three lieutenants who overthrown President Dawda Jawara, suspended the Constitution and began ruling by decree. In March 1995, a constitutional review commission was set up. The new Constitution was meant to end the “Frankenstein monster” – as the drafters described the former ruling system of Jawara.

But Jammeh’s slogans of probity, accountability and good governance may have been taken too seriously by the drafters of the constitution, estimated Sowe. Wary of executive excesses, the drafters ensured a parliamentary approval of major appointments, a security of tenure for key positions like judges, a two-term limit for presidency, an independent Office of public prosecutor, an independent Judicial service commission, among others.

“The powers of an absolute monarch”

According to Sowe, the drafters have been deceived by the military council. All the progressive clauses, meant to limit the presidential powers, were removed by the Council. Unless, “one very obvious addition [it made] is the clause that the sovereign people of the Gambia endorsed the military takeover which took place on July 22, 1994,” said Sowe.

The Council went ahead to put in the draft immunity clauses for all official acts done by the members of the military council or people acting on their behalf. Nor the National Assembly nor a court could hear cases relating to them. Only last January, the Gambia’s Supreme Court declared the immunity clauses unconstitutional.

- "Would you say that the 1997 constitution is in fact a roadmap for dictatorship?", asked TRRC’s lead counsel Essa Faal.

- "I would very much say that because if you look at the Constitution, particularly the powers given to the president, you can comfortably conclude that he is given the powers of an absolute monarch,” said Sowe.

Among the series of decrees promulgated by the military was Decree 45, which later becomes the Act establishing the National Intelligence Agency (NIA). “The director general of the NIA was given powers to issue a search warrant which is a judicial function,” said Sowe. “The decrees passed by the military council were made unquestionable before any court of law”, he added. “If you are aggrieved by the NIA, you cannot go to court.” The aggrieved party could only report to the country’s president, who could decide or not to appoint a high court judge.

After the approval of the 1997 constitution by referendum, it was reportedly amended 52 times. “Even us lawyers, did not know what (copy of the) Constitution to rely on. A lot of the changes were very self-serving,” concluded Sowe.

Brute force and draconian laws

Jammeh’s 22-year rule was a mixed dose of brute force and draconian laws. In March 2014, the ruler made a statement that exposed unambiguously his personal conception of the separation of powers: “I just want you to understand that there is nowhere in the world where the judiciary is independent,” said Jammeh, as he swore in a new Chief Justice. “We pay your salary, we appoint you, and you are part of the government - how can you be independent?”

Section 7 of the 1997 constitution would, in particular, include all decrees taken by the military council, said to the TRRC Cherno Marenah, one of the longest serving solicitor general under the Jammeh regime, on March 25.

Marenah has identified three key legislations that “attained notoriety” as they were recurrently used against public servants and perceived enemies of the former ruler. The first was a legislation on giving false information to public servants, the second on abuse of office and negligence of official duties, and the third on economic crime.

The economic crimes legislation was a military council decree, which was reportedly meant to address former corrupt employees of the deposed Jawara government. The legislation on giving false information to public servants, according to Marenah, was mostly used against whistleblowers and people who petitioned against Jammeh. The implementation of these laws, said Marenah, was depending on the president whims and caprices.

Non-compliance with court orders

In the past months, several testimonies established that Jammeh did not only have the laws, the courts, the judges, he also had the security institutions that made sure he put his opponents or perceived enemies away. The TRRC heard several testimonies about doctoring of evidences against individuals, paying witnesses even in treason trials such as the caseagainst Lang Tombong Tamba, a former Gambia’s army chief accused of a coup in 2009.

Another interference with the justice system was refusal to obey court orders, described Neneh Cham, a human rights lawyer who defended several top cases under the former regime, on March 30 before the TRRC. Cham said in cases where Jammeh had interest, her clients could not be granted provisional release.

It could go even further. On one instance, she recalled, a magistrate called Ebrima Jaiteh, now a High Court justice, had dismissed a case on the basis that he did not have a jurisdiction. Jaiteh himself was then arrested and detained. Cham also testified about denial of access to her clients in cases where Jammeh had interest, at the NIA, the police and the prison. She said they could deny having detainees, even in cases where they had them.

Intimidation of lawyers

Jammeh’s relationship with lawyers was not good from the start, recalled Sheriff Marie Tambadou, a senior lawyer who appeared before the TRRC on March 29. Following the 1994 coup, the Bar Association issued a statement condemning the military takeover, asking for a return to civilian rule. That year, in protest of Jammeh’s defiance, the Bar refused to attend the legal year, a ceremony in the Gambia for the start of a court season after recess.

“Jammeh did not like that”, said Tambadou. As time progresses, the dictator’s suspicion that the Bar does not like his “revolution” grew in strength. It further increased when, in 1996, a senior member of the Bar, Ousainou Darboe, would come to lead the biggest opposition party that will be his main challenger for 22 years, the United Democratic Party.

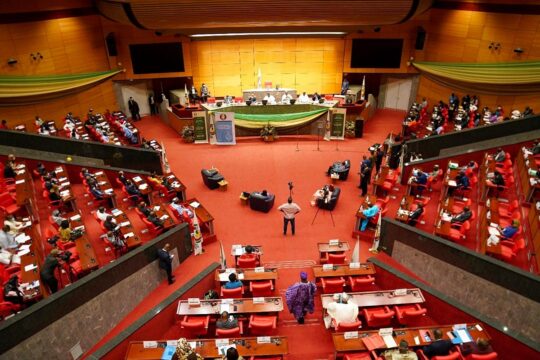

On April 6, Salieu Taal, the current president of the Gambia Bar Association appeared before the TRRC. He listed the names of the lawyers arrested under Jammeh’s regime and described how the legal profession suffered under his rule. The long list includes Antouman Gaye, a Gambian criminal lawyer who is currently leading a team prosecuting seven members of the NIA implicated in the 2016 death in custody of opposition activist Ebrima Solo Sandeng. Gaye was arrested in March 2006 and illegally detained for four days, said Taal.

Other lawyers who were arrested include current speaker of Gambia’s National Assembly Mariam Jack Denton who was illegally for no less than one hundred and eleven days without charge, said Tall. There was a court order for her release, but the government opposed it. The probe into the judiciary continues in the coming weeks. To date, the TRRC does not have decided to call a key witness to the Gambia’s judicial system abuses: Fatou Bensouda, who during the dictatorship successively held the positions of deputy director of prosecutions, principal state counsel, solicitor general and legal secretary to Jammeh, and, in 1998, attorney general and Minister of Justice, a position she would hold for two years.