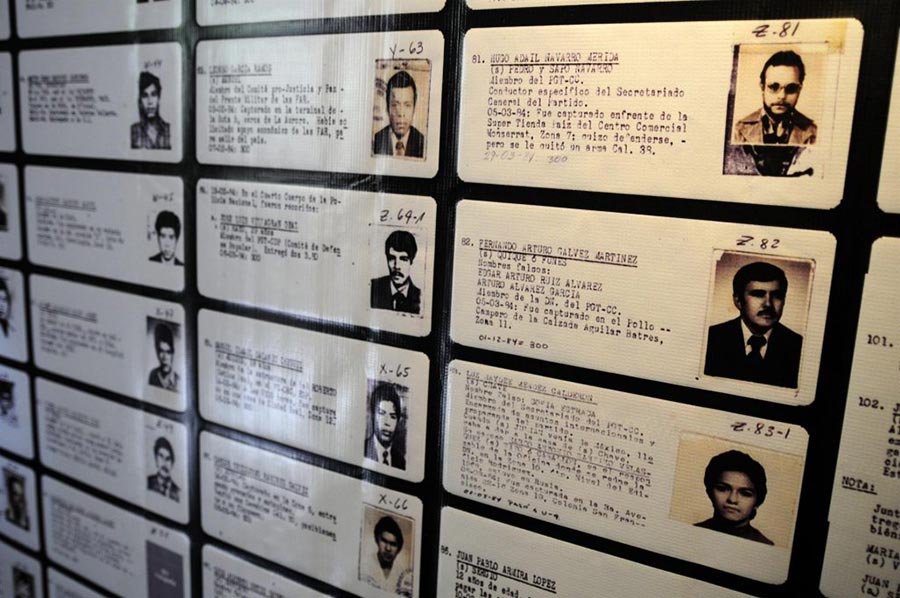

The arrest of 12 former military and police officials on 27 May in Guatemala marks a milestone in the road to justice and recovery for the victims of the chilling ‘Diario Militar’ case. The death-squad dossier, discovered over 20 years ago, is a list of the names and whereabouts of 183 individuals who were kidnapped, tortured and forcibly disappeared or executed by the military intelligence between 1983 and 1985, in the midst of the country’s internal armed conflict. Nearly 40 years after the disappearance of the victims, a pre-trial judge at a Guatemalan High-Risk Court announced, on 9 June, that 6 of the 12 officials would face trial for the grave crimes they allegedly committed. Judge Miguel Angel Galvez announced later this month that former Defence Minister Marco Antonio Gonzalez would also stand trial. At the time of the Diario Militar events, Gonzalez Taracena served as chief of the section known as ‘El Archivo’ under the Guatemalan Army High Command Staff.

But as families that have been waiting decades for justice are finally getting their day in court, mounting threats against Guatemalan judges and prosecutors threaten to derail proceedings. They are at risk of being hijacked, not only because of the politically sensitive nature of this case, but also given the history of attacks on independent judges and prosecutors in Guatemala.

In fact, one of the reasons for the delay in initiating accountability proceedings – apart from the Public Prosecutor Office’s specialized internal armed conflict unit (UCECAI) being under-staffed – lies in serious security concerns for the witnesses, judges and UCECAI prosecutors involved in this case. In the last few weeks, CSOs, human rights lawyers, victim representatives, academics and diplomats have been vocal about their concerns linked to the potential disruption of the ‘Diario Militar’ criminal proceedings. They have been sharing online, several open letters and petitions to the State of Guatemala and to the international community, calling them to ensure the independence and impartiality of the justice process. They highlight the urgent need for protection of justice actors.

To ensure that the proceedings remain independent, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) must urgently grant precautionary measures to protect the justice actors.

Political threats

No later than a week after the case was opened on 1 June, several hostile reactions were triggered. Congress representatives from the Valor party, led by Zury Rios – daughter of former dictator Efrain Rios Montt whose retrial in 2015 on charges including genocide against the indigenous Maya Ixil population was never completed –, expressed their dissatisfaction with the start of ongoing ‘Diario Militar’ proceedings. In a bold move to nip accountability efforts in the bud, Valor representatives proposed to Congress on 8 June what would effectively be a blanket amnesty bill.

If this bill passes, all perpetrators who committed serious human rights violations and atrocity crimes during the internal armed conflict period (1960-1996) will be exempt from any prosecution. The bill would also apply retroactively to over 30 former senior and mid-level military officials who were convicted for atrocity crimes and who would, as a result, be released immediately. This would represent a fatal blow to victims of mass atrocity crimes in Guatemala and would put victims, witnesses, justice actors and human rights defenders involved in these cases at risk of retaliation. A similar amnesty initiative, proposed in 2017, which sparked protests and criticism from families of victims and the international community, was dismissed by the country’s Constitutional Court in 2020.

Legal threats

In parallel, a few days after the arrest of the suspects involved in the ‘Diario Militar’ case, a denuncia (criminal complaint) was filed by the founder of the Guatemalan Foundation Against Terrorism – known for his recurrent attacks on human rights defenders. It was filed against judge Galvez and against the chief of the Public Prosecutor Office’shuman rights section, Hilda Pineda, supervising the internal armed conflict cases and representing the prosecution in the ‘Diario Militar’ case. The complaint refers to an alleged “illegal capture of veterans from the Guatemalan army”, following the arrest order given by Judge Galvez.

This is one of the many examples of what is locally referred to as “criminalization” of independent justice actors and human rights defenders in Guatemala, aimed at undermining their credibility and questioning their integrity. In the past, UCECAI prosecutors and High-Risk Court judges overseeing internal armed conflict or high-level corruption proceedings have been the target of such criminalization campaigns. They have reportedly been (mis)used as a tactic to lower the morale of independent judges and prosecutors, and to drain their human and financial resources. Dealing with the complaints distracts them from performing their work in relation to the ongoing cases.

Public threats

As if this were not enough, the same judge and chief prosecutor, along with other prosecutors assigned to the ‘Diario Militar’ case, have been subject to threats and to an intimidation campaign over social media and other means of communication. Detractors using the hashtag #SomosLaPanel (#WeAreThePanel) on Twitter – referring to the white panel truck allegedly used to carry out the abductions – have threatened that “they will pay a very high price” for arresting former military and police officials in the context of this case. ‘Diario Militar’ prosecutors have also reported being followed daily in public places by several men and vehicles trying to intimidate them. Working in such an environment takes a toll on the mental and physical health of prosecutors and judges. It is in this climate of fear, hostility and impunity that justice actors have had to carry out their work.

The IACHR can put a halt to this, by granting them precautionary measures.

An effective and accessible tool

Precautionary measures offer a solid layer of protection and a feasible solution to the High-Risk Court judges and prosecutors, assigned to the ‘Diario Militar’ case, who will continue to face serious physical threats and attacks against their integrity. According to its rules of procedure, the Inter-American Commission may request that the state concerned adopts these measures “in serious and urgent cases, and whenever necessary according to the information available”. Any person or organization may submit a request for precautionary measures in favour of a person, or group of persons, who find themselves in a situation of risk. Alternatively, the Commission can decide to grant precautionary measures on its own initiative and without any external request.

When properly implemented by the state, precautionary measures have shown to be a successful protection tool for independent judges and human rights defenders. In 2019, four Constitutional Court judges in Guatemala were granted IACHR precautionary measures, in response to personal and professional threats made against them for their position against former president Jimmy Morales’s decision to shut down the United Nations International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG). The CICIG played an important role in uncovering and prosecuting high-ranking officials, including a president and vice-president, in complex corruption cases. IACHR precautionary measures were also granted in 2013 to three Guatemalan judges who presided the Rios Montt trial, due to a reported harassment and intimidation campaign launched by Rios Montt’s supporters.

In 2016, judge Galvez was himself granted precautionary measures following several threats, attacks, and an attempt on his life, while presiding over other high-profile proceedings. He and his wife were given a security detail with protected vehicles, machine guns and antibullet jackets by the state of Guatemala. He was also included in a security plan for transportation and was put in contact with senior officials for emergency situations. It is crucial that these measures are maintained by the IACHR. By the same token, precautionary measures should be granted to UCECAI prosecutors, including chief prosecutor Pineda and other judges yet to be appointed for the trial phase of the case.

No change without challenge

Precautionary measures are not without their challenges. By its own mandate and nature, the IACHR does not provide security detail and escorts. Instead, it requests the state concerned to implement the relevant protection measures. This could be problematic in the case of Guatemala, where the advancement of internal armed conflict cases has not received the support of the ruling powers. Additionally, Guatemala’s rule of law is precarious, receiving a poor ranking of 149 out of 180 countries in 2020 on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index. But the risk of non-implementation of the precautionary measures by the state can be partially mitigated with the help of the IACHR’s monitoring mechanism, which oversees the implementation of the measures.

Another challenge lies in the timeframe for processing and granting the protective measures, given that the Commission receives thousands of requests annually. In 2018, a resolution was passed for issuing timely responses in urgent situations of irreparable harm. Judges and prosecutors in the ‘Diario Militar’ case will need to demonstrate the seriousness of the threats and the urgency of granting precautionary measures. Given the circumstances, this will not be a Herculean task.

The ‘Diario Militar’ proceedings offer a unique and historic opportunity for families of victims who were forcibly disappeared by the state to see justice done. This is essential for Guatemala’s reckoning with its past and the harm caused to the victims and families. By ensuring impartial and independent proceedings, IACHR can help to close a difficult chapter in Guatemala’s dark history.

TATIANA CHEMALI

Tatiana Chemali has been carrying out activities in support of justice processes in Guatemala since 2017, as a programme officer at Justice Rapid Response. She led the implementation of a two-year project with UNDP-PAJUST aimed at designing the human rights policy for public prosecutions and building the capacity of its internal armed conflict unit staff. She also managed projects involving technical assistance in the fields of investigations, prosecutions, criminal and military analysis. Prior to that, she had been supporting authorities in the MENA region, with UNDP and Interpol. She holds a master’s degree in Conflict Prevention and Peacebuilding from Durham University (UK).