July 14 would have been the 90th birthday of Seni Sise, the late father of Ousman Koro Ceesay, a former Finance Minister in The Gambia who was murdered in June 1995. Sise passed away in 2014. But on July 14 this year his family’s 26-year wait for justice finally bore fruit. “We wish our parents, Mr. Seni Sise and Mrs. Fatoumatta Sise were here to witness this before they passed. However, we hope they are looking down and are grateful for this day,” said Sise’s family in a statement issued after Yankuba Touray was found guilty of the murder of Ousman Koro Ceesay and handed a death sentence. “Although it has taken more than two decades, we know Allah’s timing is perfect. Today, the court has shown us that no one is above the law.”

In June 1995, Yankuba Touray was one of the senior members of the Military Council of the junta that had taken power in Gambia in July 1994. He was Minister of Local Government, while Edward Singhateh was vice-president of the Council, led by Yahya Jammeh.

« Koro [Ceesay] was a man of discipline, integrity, and service, with a fantastic sense of humor and love for his family. Today marked the beginning of a new dawn with one conviction. We trust that by the grace of God, the rest of the people who took part in the murder will be brought to justice, » said the victim’s family statement.

“A high scheme conspiracy”

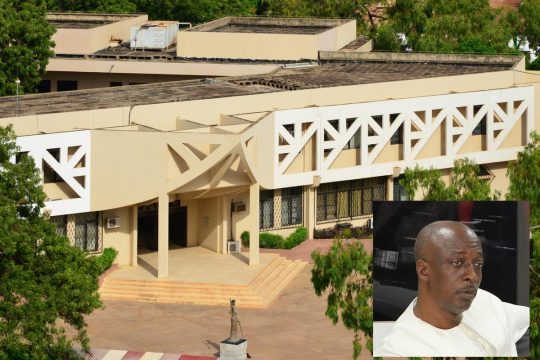

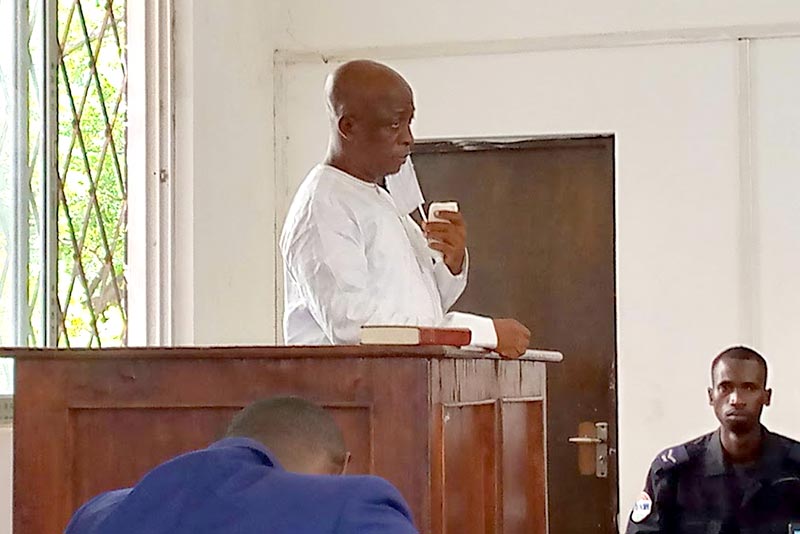

“The evidence led by the prosecution shows that there was a high scheme conspiracy hatched by Edward Singhateh, [his brother] Peter Singhateh and the accused person to kill the deceased,” said Justice Ebrima Jaiteh on July 14 in the High Court of Banjul, Gambia’s capital city. “Alagie Kanyi [a former soldier] gave evidence of how they met at the house of Edward Singhateh and were briefed by Mr. Singhateh that they were going to get rid of the deceased. His evidence shows that they drove to the residence of the accused person which at the time was empty as there was no guard or family member of the accused person in the said house,” the judge continued.

“From the foregoing reasons, the above pieces of evidence and circumstances clearly show that the accused person was involved in beating the deceased with a pestle at his residence. It is also clear from the evidence that after the deceased was struck with a pestle on many occasions, his body was placed in his official car. Furthermore, the accused person together with Edward Singhateh and Peter Singhateh left with the body of the deceased after he was killed in the residence of the accused person. Additionally, the evidence of Pa Abibu M’Baye [a retired police officer who was the crime management coordinator at the time of Ceesay’s murder and was dismissed soon after] shows that the vehicle of the deceased and that of Edward Singhateh were seen heading towards the Sukuta-Jambur Highway at around 1am of 24th June 1995. From a careful study of the evidence on record, it is apparent that the above evidence did not only show that the accused person actually took part in the crime of killing Ousman Koro Ceesay by hitting him with a pestle, he has also taken part in the scheme to dispose of the body of the deceased by burning the body beyond recognition with a view to conceal the crime, and this I shall hold as fact.”

“A historic moment for our justice system”

After Ceesay was killed, no official investigation was launched by the authorities despite preliminary conclusions of possible ‘foul-play’ reached by police officers familiar with the case and security officials, including former Interior Minister and army chief Babucarr Jatta.

“The question that begs an answer is why no investigation was launched into the death of the deceased by the accused person and his cabinet colleagues if they don’t have anything to hide from the public? Why were the people who started investigating the case dismissed from the services of the police? The obvious answer is that if the accused person had nothing to hide about the death of the deceased, investigations would have been allowed to go on without any form of intimidation towards the investigators or their dismissal as in the case of Pa Abibu M’Baye. It is our submission that the above pieces of evidence corroborate the evidence of Alagie Kanyi and inextricably link the accused person to the death of the deceased,” ruled Justice Jaiteh.

Yankuba was sentenced to death. There is a moratorium on death penalty in the Gambia since 2012 but capital punishment remains in the law of the land. For a decade, it has systematically been commuted to life imprisonment.

It was the first time Gambians could see a verdict livestreamed and – as they have been doing with public hearings before the Truth, Reconciliation and Reparations Commission (TRRC) in the past two and a half years – they went to several social media sites to watch it.

“The rule of law has taken its course on Yankuba Touray. And it is quite a great day for justice. It is a historic moment for our justice system,” said Sheriff Kijera, chairman of the Center for Victims of Human Rights Violations, an organization supporting Jammeh’s victims.

What’s in the verdict for Edward Singhateh and his brother

Yankuba Touray’s trial for the murder of Ceesay started in November 2019 and it is the direct result of the work of the TRRC. It was prompted by Touray’s refusal to testify before the TRRC on June 26, 2019, on claims that he has constitutional immunity. His uncooperative behavior with the TRRC prompted a national outcry. The Commission ordered his arrest on charges of contempt. And the then Justice Minister Abubacarr Tambadou asked that he be charged with murder. In January this year, the Supreme Court ruled that Touray had no immunity from prosecution for the murder of Ceesay. A lot of the evidence in the case was first detailed before the TRRC.

Former vice-president Edward Singhateh himself appeared before the TRRC in October 2019. He denied any knowledge of the murder, while his orderly and his driver, Lamin Marong and Lamin Fatty, said they had dropped him at Touray’s house on the night of the murder. Singhateh assured, to the contrary, that he was at home. He said Marong and Fatty had been “kicked out” of his house, suggesting they have a motive to lie against him. But Jangom, the guard commander at Touray’s house, also said that after returning from their patrol, he saw Singhateh at Touray’s house, smoking. Singhateh retorted that he does not smoke, suggesting Jangom was also a liar.

The Gambian law does not provide for secondary participation in criminal matters, which means that if one willingly takes part in the commission of an offence, he or she is a principal player. For many legal commentators, if a charge stands against Yankuba Touray, the Singhateh brothers may have a tough fight to fend it off if they are charged in turn.

Waiting for the Truth Commission recommendations

For Gambia’s rights activists, the verdict is a signal that the time has come to pursue criminal justice for other crimes.

“This verdict is a huge relief for victims that the road to justice may be long but it shall come to pass one day. It gives hope that ultimately all perpetrators, especially those unrepentant and remorseless such as Yankuba Touray himself as well as Edward Singhateh and Yahya Jammeh, will face justice for their heinous crimes,” Gambia’s leading human rights activist Madi Jobarteh told Justice Info. “While I do not support the death penalty, the ruling however is significant in the quest to give victims and survivors the last laugh.”

Gambia is about to move into a post-Truth Commission era. The TRRC is expected to submit its final report to President Adama Barrow before the end of the month. And the report should include recommendations for the prosecution of a number of individuals. Touray is the most high-profile member of the former junta to be sentenced for a crime committed under Jammeh. But many other former officials and perpetrators appeared before the TRRC and it doesn’t protect them from prosecution, even when they cooperated. Touray’s verdict comes in a context of a pre-campaign for presidential elections where there are many thorny questions about the current government’s political will in ensuring justice for Jammeh-era crimes. Debates on what to do with the transitional justice process once the TRRC has finished its work are ongoing. Touray’s trial may foretell how controversial the situation may look like in the coming year when it comes to post-TRRC prosecutions. Attacks against the judge in the case – who was himself victimized under Jammeh and a witness before the TRRC last May – are another sign of the political tension surrounding such trials. For victims’ rights activist Kijera, however, the verdict handed down on Yankuba Touray “has reinforced the commitment of victims to pursue justice for others”.