Behind the weeds and neem trees, lies the Abomey Museum. A temple of several centuries of history that is difficult to see. You have to open your eyes and read the rusty sign "Site of the Royal Palaces of Abomey inscribed on the World Heritage List" to be convinced. A few metres away from the sign is a long mud wall with a few cracks in it and a vestibule in the middle. This is the entrance to the museum. It leads to a large courtyard on laterite soil. Photography is not allowed in most of the museum, says the guide. Visitors are not allowed to enter the buildings under construction, which are hidden by sheets of metal, a little way back. The construction site is not open to journalists either.

The tour leads the ten or so visitors to the Throne Council. It is a white building under a rusty roof, with bas-reliefs dating from the 18th century - animal heads and other war trophies embedded in the wall. For about 30 minutes, we walk through a dozen rooms containing display cases of weapons and personal effects of former rulers of the Danhomè kingdom. These relics are well-guarded, under cameras perched on the bamboo ceilings.

A 50-million euro project

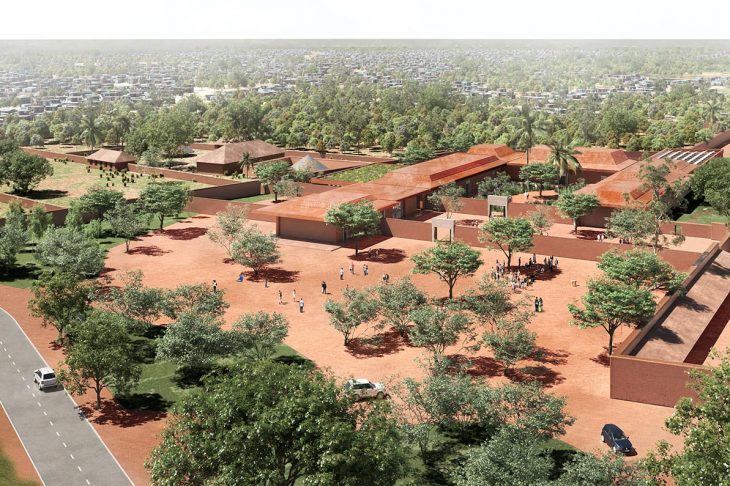

The hut of the queen mothers appears the most dilapidated, topped with a cone-shaped roof with holes. The cement-coated mud walls that separate the different courtyards are cracked in places. In short, the overall appearance of the cultural heritage of this historic town, located about 130 kilometres from Cotonou, the capital of Benin, is not the most glowing. And so it is to give a new face to this place that the project of the Museum of the Epic of the Amazons and Kings of Danhomè and the development of the palatial site was born, explains Alain Godonou, director of the Museums programme at the National Agency for Heritage and Tourism Development (ANPT). 50 million euros - of which 15 million come from the Beninese state budget and 35 million from France, including 25 million in the form of a loan, according to an agreement made public on 3 June - for a site that extends over 47 hectares, have been raised to build a museum to international standards and to rehabilitate the four royal palaces of Behanzin, Guézo, Glèlè and Agoli Agbo, which together occupy an area of 14 hectares. Four architects - two Beninese, one French and one Franco-Cameroonian - are working on the site, says Godonou, a pioneer in the reflection on the restitution of cultural property to Africa.

For it is here that, about 130 years after their looting in this royal city in what is now Benin, 26 famous works of art, stolen in 1892 from the kingdom of Abomey by French colonists under the orders of General Alfred Dodds and exhibited since then in the museums of the former coloniser, are to be returned.

The impatience of the inhabitants

Near the cobbled road adjacent to the front of the museum, we pass four old men, sitting in the shade of a tree and visibly enjoying the fresh air. After the traditional greetings, we start a short discussion about the restitution of the art from the kingdom of Danhomè. "We've been hearing about this return for over four years, but we've seen nothing," one of them complains. "They said that the French MPs are voting on a law. We want to see concrete things", says a second. The third complains about the current state of the historical museum. "Look behind you! All this weed in front of our museum, which should house these works that are dear to us. We heard on the radio that it will be rehabilitated. They are doing study after study to build the museum in the courtyard of the Amazons, over there. But we can't see anything.”

The inhabitants of Abomey seem to be stamping their feet with impatience. They are also quite upset about the current appearance of the museum. "Go over there and see for yourself. Ask the curator. He's inside," they suggest.

30 October 2021. This is the date set for the return to Benin of the precious regalia, symbols of royal power. The boxes containing them should land in the night at Cotonou airport, via two separate Air France flights.

But these statuettes, staffs (a royal sceptre, one of the seven symbols of authority of the Fon king), and thrones, will not immediately return to their place of origin. In Abomey, the infrastructure to house them is still only a "model". The major works are not due to start until March 2022 and should last three years, says Godonou.

Ouidah, the treasure’s first stop

The day after their arrival, the 26 royal pieces will first be transferred to the former Portuguese fort in Ouidah, a site specially rehabilitated to house them temporarily.

In Ouidah, work is already underway. The deafening sound of electric saws can be heard from the entrance to the old fort. The construction site is surrounded by sheets of blue metal. The new entrance is gradually taking shape. It is reached by a small staircase with wooden steps and ramps inlaid with large pieces of gravel. This staircase leads to an esplanade lined with emerging lawns. The landscaping is underway.

This 8,000 sqm site is made up of two lots, that of the construction of the International Museum of Memory and Slavery (MIME) and that of the rehabilitation of the fort. This second lot was started two and a half years ago. The structural work has already been completed, says Godonou. The art pieces to be repatriated will be temporarily kept in the Portuguese fort. The fort consists of three compartments: the governor's house, the barracks and the chapel. Before being transferred to the temporary exhibition area (the governor's house), the 26 works will be installed in the barracks. When we visited in mid-July, the framework of the barracks was in place under a red tile roof. On the side of the governor's house, a one-storey building of 250 sqm, the workers were working on the framework while the plastered wall was awaiting its final white cover. Behind this house is a garden decorated with flower pots and orange trees, next to large mango trees, among others.

The preparations are not just about infrastructure. Training plans have been designed to strengthen the capacities of Beninese curators and other actors involved in the project, explains the Minister of Tourism, Culture and Arts, Jean Michel Abimbola. According to forecasts, the ad hoc training will be completed before the return of the 26 artefacts. "We will have two Beninese professionals who will go to France and return with these works, with French professionals," says the minister. Because beyond the 26 works, it is a whole training policy that is being implemented so that Beninese cultural heritage professionals are up to speed. The project on the restitution of cultural property is also dear to the government's heart because, says the minister, it will provide jobs. "It is a policy of mobilising resources for the benefit of young people, a policy of cooperation, of reaffirming culture and our heritage," he continued.

Benin is a pioneer in requests for the restitution of cultural property looted during colonisation. It was in Cotonou from 30 June to 3 July that the first meeting of the regional monitoring committee of the 2019-2023 action plan on the return of African cultural property took place, organised by the Community of West African States (ECOWAS), which brings together 15 West African states, including former French, English and Portuguese colonies.

The action of the descendants of the royal family

The 26 works soon to be returned will now belong to Benin's national heritage. But in the past, they were the property of the kingdom of Danhomè. This kingdom is nowadays limited to the city of Abomey, in the south of the country. And if this city, like the 70 others in the Republic of Benin, is ruled by a mayor, it retains its tradition and maintains its royalty.

On the throne of Abomey since 2019, Dah Kêfa Sagbadjou Glèlè is one of the descendants of the kings plundered during the colonial period. On 19 June 2021, he received us in his private palace, a concession with earthen fences and rooms built of cement. Draped in a large loincloth, wearing necklaces and holding a recade, the king welcomes us in his living room, seated under a parasol held by a woman. At his feet sits a wooden lion sculpture. "I am very happy that these works of art, which belonged to my ancestors, are coming back to our land," he says. "On the day of their return, I will be at Cotonou airport to welcome them," he announces, opening his arms as if he were already embracing the precious goods. This descendant of the great Fons sovereigns - who says he is consulted in the process of repatriating the works - is waiting for the construction work to begin on the Abomey museum so that the artefacts can be kept there after their stay in Ouidah.

Claiming his rightful title, one of the princes of the kingdom of Abomey, Serge Guézo, had written to French President François Hollande on 15 April 2015 to claim the artefacts from the kingdoms of Savè and Abomey. He had obtained an audience with the French head of state's Africa advisor. The prince, who lives partly in France, is convinced that his approach has had an impact on the process of restitution of the royal pieces and it is therefore a source of pride for him to see his wish come true. It is "a big step, which has symbolic value for our African continent", he says.

But it is not entirely satisfactory, he adds. In addition to the 26 works, Prince Guézo is taking action to ensure that the many other objects and human remains in French museums are returned to their countries of origin. He also stresses that the 26 expected works must be the object of rituals because the time spent in a foreign land would have desecrated them. Questioned on the issue, the minister in charge implied that all the necessary ceremonies would take place when the works were received on Beninese soil.