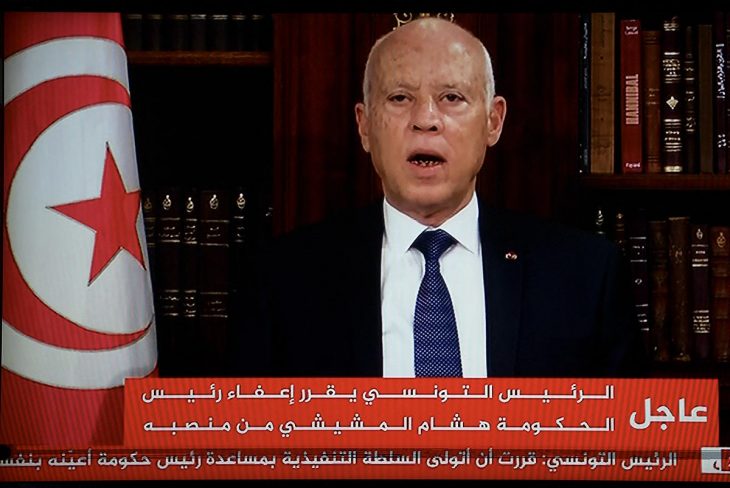

On July 25, following a day of demonstrations sparked by government handling of the Covid-19 and economic crises as well as resentment against the political parties in parliament, President Saïed triggered Article 80 of the Constitution and declared a state of emergency. He dismissed the prime minister, suspended the activities of parliament and assumed full powers "for one month, renewable" before extending them on August 24 "until further notice”.

On the evening of July 25, there was popular jubilation at the "coup" of this president who is a trained lawyer and is anti-system. But more than 50 days later, many human rights NGOs worry that the president's unilateral decisions, his salvo of decrees, administrative and judicial measures threaten a return to the authoritarian rule long exercised in Tunisia up to the 2011 revolution.

Wounded of the revolution in despair

Since then, several presidential decisions and addresses to the people have led to fears of a setback, or even abandonment of the transitional justice process, which is already experiencing delays and blockages due to lack of political will.

On July 27, President Saïed dismissed Abderrazek Kilani, who had been chairing the General Authority of Martyrs and Wounded of the Revolution and the management committee of the Dignity Fund for Reparation and Rehabilitation of Victims of Tyranny, without appointing anyone to replace him.

The Authority provided the handicapped with catheters, medicines and medical aids, even if it did not take into consideration all the dimensions of their suffering, in particular their trauma, professional and social fragility. This category of victims, the most fragile, is now left in despair. The self-immolation of a young, injured revolutionary, Neji Al Hafiane, in early September was a tragic illustration of this.

Lawyer Lamia Farhani, president of the association Awfiya (Faithful), defends the rights of the injured and families of martyrs of December 17, 2010-January 14, 2011. "If the Authority led by Kilani is suspended, who can the victims turn to?” she asks. “It’s not surprising that there are such tragedies. I receive daily calls for help. Threats of suicide are not lacking either. I am particularly worried about Kaïs Ayadi, father of three children, who says he has 'only death to look forward to'. Unfortunately, my association doesn’t have the resources to provide emergency aid to survivors of the violence of the revolution.”

A populist decision

If the president has decapitated these two transitional justice institutions in one fell swoop, it is probably because of the bad press that reparations have with many Tunisians, explains Farhani. She says Kilani was dismissed to satisfy groups on social media who, on the eve of July 25, urged that there should be no compensation for Islamist victims, whom they accused of emptying the state coffers, monopolizing public administration, and taking advantage of the ruling coalition’s generosity in the post-revolution years. These groups were formed after Abdel Kerim Harouni, chairman of the Shura Council (the Islamist party's internal parliament), issued an ultimatum to the government on July 1 to inaugurate the Reparations Fund.

Professor of public law Wahid Ferchichi, who is president of the Association of Individual Rights and Freedoms and an activist for transitional justice, does not agree. “Transitional justice is not part of Saïed 's electoral programme," he says. “He has never talked about accountability of the state security apparatus. On the other hand, his plan to recover public funds and use them to develop the regions is a kind of penal transaction: peace with the businessmen suspected of corruption in exchange for cash.

When he came to power after the October 13, 2019 elections, Saïed ignored the victims' urgent requests to organize an official apology ceremony on behalf of the Tunisian state. "Such a gesture by the president could have instilled hope and optimism among the 62,000 victims who submitted their cases to the Truth and Dignity Commission," says Ridha Barkati, brother of opposition activist Nabil Barkati, who died under torture in 1987.

“Saïed relies on the police and army”

Sihem Bensedrine, former president of the Truth and Dignity Commission, says another indicator is the president’s appointment to key Interior Ministry positions of senior officials Sami Yahiaoui, involved in the death and abuse of peaceful demonstrators in 2008, and Khaled Marzouki, who was involved in police violence in Tala and Kasserine during the revolution. In August, President Saïed gave them management positions in the Special Services and Intervention Units respectively. Following protests from civil society, Marzouki was removed on August 24, one week after his appointment. Yahiaoui was kept at the head of Intelligence. Since 2018, both men have been on the list of defendants before the transitional justice Specialized Chambers.

“Saïed relied on the police and army to organize his coup,” says Bensedrine. “Hence the impunity enjoyed by those two bodies. The police unions are the masters of the country today, they have power over people’s freedom of movement and take revenge on all those who have bothered them before, especially the Truth and Dignity Commission. It seems that all the Commission’s staff is on the red list and forbidden to travel."

Threats to the Specialized Chambers

On February 8, four UN rapporteurs wrote to the Tunisian government expressing concern about blockages in the transitional justice process. They denounced campaigns denigrating the work of the Truth and Dignity Commission to justify a new law on transitional justice, which would grant amnesty to alleged perpetrators. "We would like to recall that international human rights standards require states to guarantee the legacy of truth commissions and to protect their members from unfounded defamation," the UN rapporteurs wrote.

On September 11, one of the president's advisors, Walid Hajjem, said on satellite channel Sky News Arabia: "Saïed is considering revising the political system to establish a presidential system, a proposal that will be submitted to a referendum. This means suspending the Constitution and adopting other mechanisms for running the state. The political regime put in place by the 2014 Constitution is no longer appropriate."

The president's intention to amend the Constitution has transitional justice activists in a cold sweat. Bensedrine worries that it could mean the disappearance of a crucial safeguard, Article 148 of the Constitution, which commits the state to guarantee the continuation of the transitional justice process. "Worse still, if this Article is discarded, the Specialized Chambers will no longer have any reason to exist. The whole process of fighting impunity is at stake," she says.

The populist president is an avowed supporter of "December 17" (2010), date when the revolution was triggered by regions of the interior and the poor, and is opposed to "January 14" (2011), date when the elites and political parties entered the scene. He sees the Constitution and transitional justice as institutions that have come to dampen and divert the revolution.