Dr. Alaa Moussa doesn’t need the help of a translator. His German is not perfect, but he addresses the judges with polite phrases, and talks confidently about his work as a doctor for orthopedics and trauma surgery in Syria. The defence lawyers must have known that the defendant can make a good impression. “After a lot of thinking, we have decided that he should speak for himself”, they say on the morning of the second day in court. “We believe that you should get to know him.”

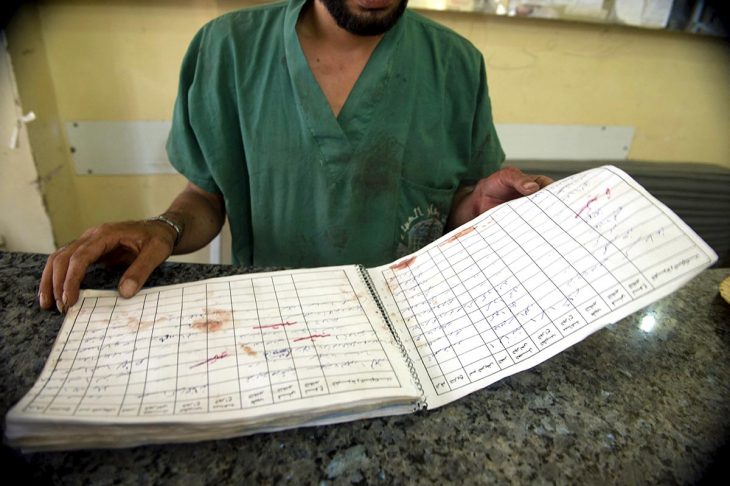

Their client is a 36-year-old Syrian man in a slim navy-blue suit and white shirt, with bags under his eyes and a neat haircut. He had started to work in Syria’s military hospitals as an assistant doctor just before these hospitals became places of torture and death – places where bodies from different secret service branches were gathered and documented, then carted off to mass graves.

On the 19th of January, just a week after the final verdict in the Al-Khatib case, Germany has opened its second trial on crimes against humanity in Syria. At the Higher Regional Court in Frankfurt, Alaa Moussa is accused of having tortured 18 prisoners in 2011 and 2012 in military hospitals in Homs and Damascus, as well as in a military intelligence prison. In addition, he is alleged to have killed a prisoner by giving him an injection. According to the indictment, this was done “to demonstrate his power and at the same time to suppress the rebellion of a part of the Syrian population.”

Like the first trial in Koblenz, the one in Frankfurt is made possible by the principle of universal jurisdiction, that allows countries to prosecute the gravest crimes against international law anywhere in the world. While the Al-Khatib trial dug deep into the secret services’ torture and prison system, this second trial will shed light on another piece in the puzzle of Syrian state crimes: the special role that doctors and hospitals played in oppressing and punishing the opposition.

Arranging himself with the Assad regime

Alaa Moussa had just finished his university studies and worked in the military hospital of Homs for a year, when Tunisia’s and Egypt’s revolutions swept into Syria and brought thousands of protesters to the streets in the spring of 2011. His career in different military hospitals in Syria enfolded during a time when the regime waged its widespread and systematic attack against the civilian population – and Alaa Moussa is said to have participated in it. According to the indictment, he worked in military hospital N° 608 and the prison of secret service branch 261 in Homs, as well as military hospital Mezzeh in Damascus between April 2011 and the end of 2012. During this time he allegedly abused detainees by beating and kicking them, whipping them with medical instruments, stepping on open wounds, operating without narcosis and setting body parts on fire. One patient, who had an epileptic fit, is said to have died after Moussa gave him a pill. Another was killed intentionally through an injection, according to the indictment. In the most harrowing of the crimes, the doctor allegedly poured alcohol over a teenage boy’s genitals and set them on fire. This would also make him guilty of depriving another person of the ability to reproduce. “He bragged that he had invented a new method of torture”, the prosecutor read out on the first day of the trial.

When he was arrested in June 2020, Alaa Moussa was living in Germany with his wife and two children, and working as a doctor in the small Western German town of Bad Wildungen. He had long been eager to work abroad and had been learning German for years before obtaining a visa in 2015. Unlike thousands of Syrian refugees, he did not leave the country to seek safety from the war or the regime’s violence, but for an opportunity to advance in his career. Regarding his political convictions, the defendant admitted in court that he had arranged himself with the Assad regime in order to have a successful life. “But neither my family nor I were ever ardent supporters of the regime”, he added. When the protests started in 2011, he said he was on the verge of joining. But being part of the privileged Christian minority in Syria, he was soon taken aback by protesters’ sectarian chants. “I was against violence from both sides”, he said.

“Doctors kill in a smart way”

Alaa Moussa has denied any involvement in the alleged crimes. He believes that the accusations are a kind of conspiracy against him as a Christian, a theory he is planning to elaborate on during the coming weeks in court. In his statement on the first days of the trial, he gave a detailed account of his career path. He said he left Homs for Damascus in November 2011, where he started a new job at Mezzeh military hospital, known by many Syrians as the “human slaughterhouse”. He claimed he never returned to his former workplace, where many of the crimes allegedly took place. He admitted seeing staff and secret service officers abuse prisoners in the hospitals, but denied ever participating. “I felt sorry for the prisoners”, he said, adding that he could not have done anything to help them if he didn’t want to end up in their place. “We were not allowed to exchange a single word with the patients”, he said. “We were all under the control of the secret services.”

Annsar Shahhoud, a Syrian researcher based in the Netherlands, has heard this claim before. For her Master thesis at the Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide studies in Amsterdam, she interviewed 22 doctors and nurses, many of whom were perpetrators of medical violence in Syria. “I saw it, but I wasn’t involved in it – a typical excuse”, she says. According to her research, a number of doctors in Syria incited, organised, committed and legitimized violence. “They select victims and choose the patients who should be killed. They know how to implement torture and how to starve someone. They kill in a smart way”, she explains. Especially in Syria, where the president himself is a doctor, members of this profession had always worked together closely with the regime, abusing the trusted relationship that usually exists between a doctor and their patient, according to Shahhoud. “The nature of medical violence is private and intimate. Doctors applied it in closed rooms, not out in the open”, she says – a point that will not make the collection of evidence in Frankfurt any easier.

Hospitals as places of horror

“Unlike in Koblenz, this defendant may not have been officially incorporated into the military hierarchy”, says plaintiff lawyer René Bahns. Alaa Moussa has stated that he was a civilian doctor working in a military hospital, therefore it might be more difficult to prove that he acted in line with the regime’s widespread and systematic attack – a crucial aspect, if the court wants to define the alleged crimes as crimes against humanity. “But regardless of his official function, I completely rule out the possibility that he abused prisoners at his own discretion”, says Bahns, who represents one of three joint plaintiffs in the case. His client was detained and abused at the military intelligence branch in Homs together with his brother. His brother was the patient who died after suffering from an epileptic seizure. For this plaintiff, it is especially important that the trial sheds light on the role of military hospitals in the Syrian torture system. “I am convinced that they were part and parcel of the regime’s terror machine”, says Bahns, pointing out that this had come up more than once in the Al-Khatib trial.

In the trial that just concluded in Koblenz, military hospitals had been portrayed as places of horror. One detainee had described how he was chained to a bed and abused for days and nights on end, until he was left out on the street to die. Another survivor described that the Damascus Hospital turned into a prison ward and how the corridors filled up with armed secret service officers. And one anonymous witness described how he and his colleagues picked up dead bodies from the military hospitals several times a week and took them to mass graves – a fact corroborated by the Caesar photos, most of which were taken at military hospitals Mezzeh and Tishreen in Damascus. According to lawyer Bahns, however, the findings of the Al-Khatib trial will not save the judges in Frankfurt much work. “They will have to make their own investigations into the widespread and systematic attack”, he says, especially since the Koblenz verdict is still under appeal and has not been published in writing yet. Bahns expects the Frankfurt trial to be a very lengthy one.