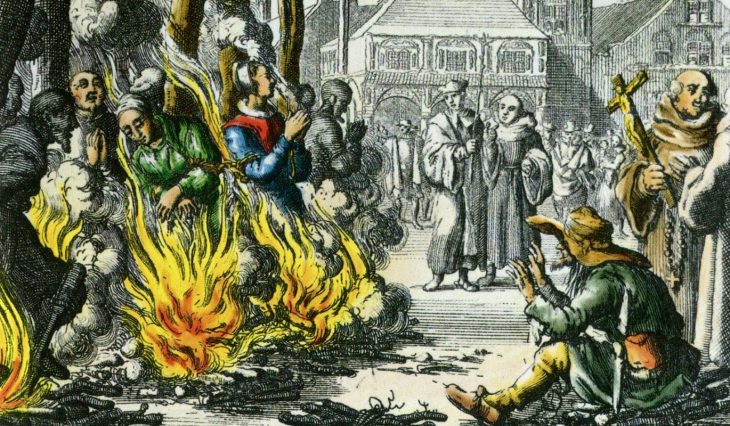

Do they fly on broomsticks? Glow in the dark? Dance with the Devil? Obviously not. Witches have been a subject of fascination for centuries in myths, fairy tales, films, even some well-known comedy sketches and series. But while they may be fun in fairy tales, accusations of witchcraft led to the torture and execution of at least 50,000 people in Europe in past centuries. Some 60-70% were women, according to Martine Ostorero, associate professor of medieval history at Switzerland’s University of Lausanne, and there is no doubt that medieval society was misogynistic. But the rest were men, sometimes children. Ostorero says these people were subject to “extraordinary justice” because their crimes were considered to be the worst. They were convicted on confessions, often extracted under torture, because “obviously there was no evidence,” she told Justice Info. Many of them were burned at the stake.

Witches were persecuted by the Church, State or local communities for being perceived as different, rebellious or not in line with the dominant religious beliefs. Often they were blamed for things like natural disasters, famine and child deaths. Did any of these victims actually practice “witchcraft”? “Like today, there were healers, people who had secret remedies, which met a social need,” says Ostorero. If the remedies didn’t work, perhaps they were more likely to be accused of witchcraft. But, she says, it’s hard to know how many of those killed were in this category, because interrogations tended to focus on such things as whether they loved the Devil or ate children. Movements to pardon the “witches” executed in the past tend to see them all as innocent victims.

Victims of misogynistic persecution

On January 26 this year, Catalonia’s regional parliament passed by a large majority a resolution to rehabilitate the memory of more than 700 women who were tortured and put to death centuries ago. Spanish historians have discovered that Catalonia was one of the first regions in Europe to carry out witch hunts. It was also considered one of the worst areas for executions.

Pro-independence and left-wing groups who led the campaign say the names of the women now pardoned were only recently discovered. They believe these women were "victims of misogynistic persecution" and want their memory honoured by naming streets after them. "Before they called us witches, now they call us 'feminazis' or hysterical or sexually frustrated. Before they carried out witch hunts, now we call them femicides," said regional deputy Jenn Diaz of the left-wing ERC, which is one of the largest parliamentary parties and holds the Catalan presidency.

Further north, the Witches of Scotland campaign, founded by barrister Claire Mitchell and writer Zoe Venditozzi, wants the Scottish parliament to grant a legal pardon for an estimated 2,500 people, mainly women, who were convicted and executed under Scotland's Witchcraft Act, in force from 1563 until 1736. They also want First Minister Nicola Sturgeon to offer an apology on March 8, International Women's Day, and for a national memorial to be erected to the victims.

An estimated 2,558 people executed in Scotland

“It will right a historical wrong, so when historians look back at us they will see that in the 21st century we recognised it was wrong,” Mitchell told Justice Info. “It will also send a clear signal that could help people still fighting modern-day witchcraft accusations.”

Mitchell is a lawyer working particularly on miscarriages of justice and how they can be righted. She is clearly inspired by that, and her research into the Witchcraft Act. She says she was also driven by just walking around the Scottish capital Edinburgh and realizing how little women are represented in street names and public places – either for their achievements or the terrible things that were sometimes done to them.

An estimated 3,837 people were accused of witchcraft under Scotland’s Witchcraft Act and two-thirds of them were executed, often strangled and burned. That means 2,558 people, according to Witches of Scotland, and 84% were women. Its website gives some interesting insight into where some of the myths may have come from: “The signs associated with witches (broomstick, cauldrons, black cats, black pointed hats) were actually things used by “alewives” – women who brewed weak beer in medieval times as a method of combatting the poor water quality at the time,” it says. “The sign above their door was a broomstick to let people know they could buy beer, they used large cauldrons for brewing, cats were kept to keep the mice at bay and the black pointed hats were used to make themselves easily identifiable at market.”

In the wake of the “#MeToo” movement

Mitchell says the campaign in Catalonia was actually inspired by the Scottish campaign but had more funding and was able to move faster. But she is hopeful the Scottish parliament will also pass legislation this year introducing a pardon for the executed witches. Scottish National Party (SNP) member of Scotland’s parliament Natalie Don plans to introduce a private members’ bill on this. Mitchell says the bill has support from the SNP, Green and Liberal parties and is now undergoing a period of public consultation.

Campaigners have not yet received any response from the First Minister or government about the prospect of an apology on March 8, but again Mitchell remains optimistic. Asked if it is likely that the government will apologise for something not its responsibility, she argues that there are precedents. She cites, for example, Scotland’s 2019 pardon for all gay and bisexual men convicted under abolished laws criminalizing homosexuality.

So why now, centuries after the events? Clearly it comes at a time when Europe is examining its past, particularly its colonial past. It also comes in the wake of the “#MeToo” movement, with women speaking out against injustice. But Swiss historian Ostorero thinks there may sometimes also be political reasons. “These initiatives are often led by feminist and left-wing groups wanting to assert the rights of minorities,” she says. “But in the case of Catalonia and Scotland also pro-independence movements. They want to show they are ready to recognize errors of the past when the central government is not.”

The last witch executed in Europe was in Switzerland

Yet these are not the only places to have made such moves. Switzerland also executed “witches” in the Middle Ages, at a time when it was not only small but a weak federal state. Ostorero says that although there were many reasons, it was often a way for authorities to try and keep control through terror. Indeed, Switzerland persecuted presumed witches longer than any other country in Europe. In relation to its population, it also executed the most people for the crime of witchcraft.

The last “witch” to be executed in Switzerland and Europe was Anna Göldi in canton Glarus in 1782. She was decapitated in a public square. She was also the first to be rehabilitated in Switzerland, being posthumously “exonerated” by the Glarus cantonal parliament in 2008.

Several other Swiss cantons, especially in French-speaking Switzerland where the persecutions were worse, have also taken similar steps in the last 15 years, says Ostorero, including Fribourg and Geneva. In canton Vaud, a plaque was erected just over a year ago at the Ouchy castle in the cantonal capital Lausanne to the memory of one of the first “witches” persecuted in Vaud, Jaquette de Clause. It was in the Ouchy castle, by Lake Geneva, that she was imprisoned. Ostorero, who was consulted on this initiative, says it is part of a move by the Lausanne authorities to dedicate more streets and public spaces to women.

In Norway, the northern town of Vardø opened a monument in 2011 commemorating the trial and execution in 1621 of 91 people for witchcraft.

And of course, it was not just Europe. In the US, the Massachusetts legislature in November 2001 passed an act exonerating all who had been convicted in the Salem witch trials and naming each of the innocent.

Fake news and modern-day witch hunts

So what is the relevance of such pardons today? Ostorero thinks it is an occasion for historians to plunge more deeply into the complex nature of these witch hunts. But more than that, she says there is a warning for our times. Most of these so-called witches were convicted on rumours, while rumours, “false information” and conspiracy theories are still causing harm today. She points to the example of QAnon, the right-wing, pro-Trump conspiracy theorists who were at least partly behind the January 2021 attack on the US Capitol.

And then, unfortunately, witch hunts are not a thing of the past, as recognised by a UN Human Rights Council Resolution adopted in July last year calling on all States to fight the practice. Leo Igwe, a campaigner at Humanists International against modern-day witchcraft accusations, says this problem is still rife in many parts of the world, including in Africa, India and Oceania. Those targeted are often elderly people -- especially women -- and children who have become a burden to their overstretched families and communities, he told Justice Info from Nigeria. He blames government failure to provide the necessary amenities, social benefits and free medical care.

Asked what happens to the victims, Igwe cites some examples. “Children are sent to centres where they are subject to ‘exorcism’. They may be made to fast, tortured and beaten. In southern Nigeria they may be beaten with a hot iron, causing permanent injury and harm.”

So would a pardon in Scotland for “witches” of the Middle Ages help the campaign in Africa now? Igwe is convinced it can have strong resonance, especially with modern technology and the fast spread of information. “It sends a strong message that what happened in Scotland 300 years ago is wrong and what is happening now in Ghana, for example, is wrong -- that people targeted by witchcraft accusations are victims, it’s a miscarriage of justice and they deserve an apology.”