Concrete is eating up all the spaces around the Senegalese capital. To go and meet this violinist we had to take the brand new TER train from the centre of Dakar to the end of the line at Diamniadio, the “second capital” that is under construction. After a short taxi ride from the glass-covered station smelling of fresh cement, Harouna Daouda Dia welcomes us to his village, which he says had four Fulani families when he was born there in 1960.

Tarmac has not come yet, but the concrete buildings have already arrived. Their grey skeletons encircle the goats and the boys playing football in a cloud of red dust. In the musician's plot, empty bags of "Sahel cement" rest in the corner of the cinderblock wall against which Harouna leans to receive his visitors in an improvised outdoor living room on a red carpet. Harouna is a bambaado: a respected griot whose life is devoted to singing during ceremonies, to telling the story of his people and the Fulani kings. His voice is that of the nianiérou, or ritti, a one-stringed violin whose soundboard is made of lizard skin.

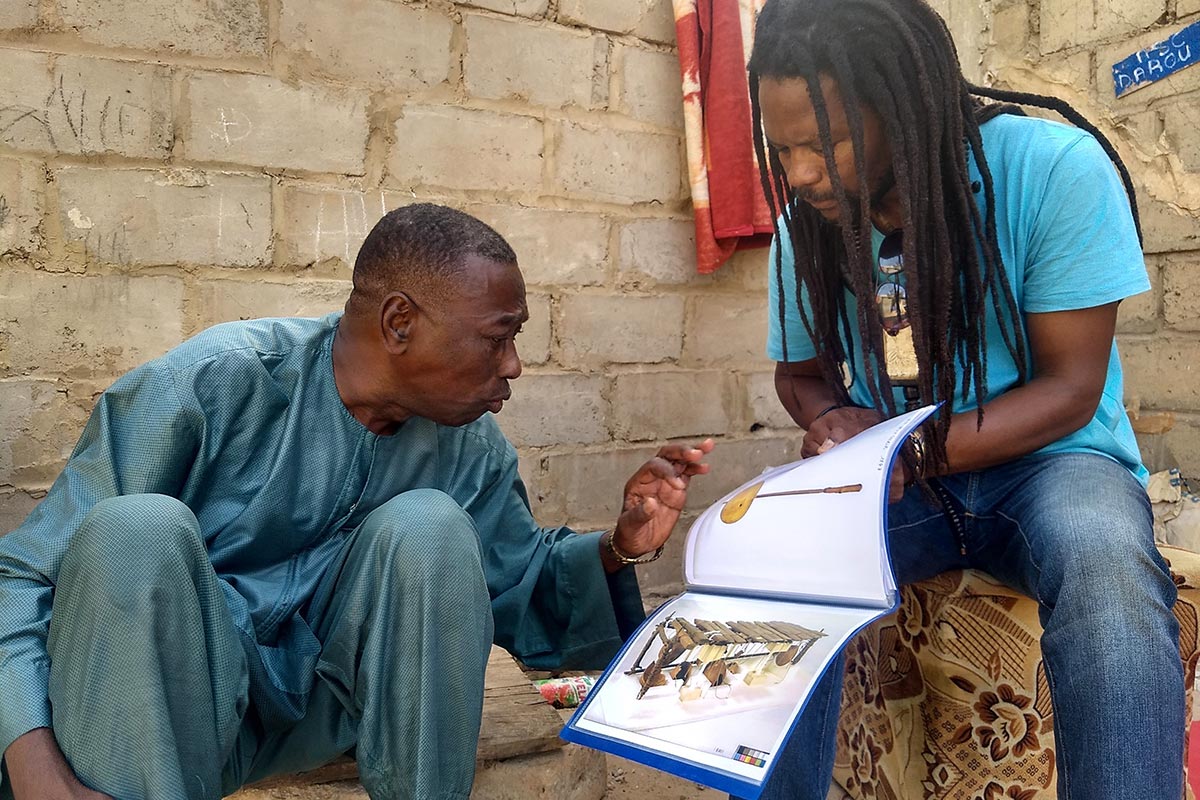

The interview takes place in Pulaar, the Fulani language spoken throughout West Africa and beyond. Harouna’s nephew Issa, who has come to see him with photographs of instruments taken in Senegal during the colonial era, interprets for us. Issa Dia works for the NGO Alter Natives, created by conservation professionals who seek to bring together young African and French people "to support the return of African heritage”. Issa shows his uncle a photo of the Cité de la Musique curator in Paris, who wanted to know more about an instrument in his collections. It had been identified as a ritti taken in 1847 in Gandiol, near the mouth of the Senegal River. The person who collected the object is, a priori, beyond suspicion of theft since he is Victor Schœlcher, a French politician famous for having campaigned for the abolition of slavery.

Schœlcher got it wrong

But Harouna grimaces. “The Fulani violin is not like that," he says. “It’s not a lizard skin, it’s a goat skin..." The master of the ritti drinks his tea, clears his throat, while his nephew sets up a camera for a recording for the Cité de la Musique. After absorbing the fact that this is an object of the nineteenth century, the musician tells us more: "This is a Moorish lute or oud, because we see there can be four strings,” says Harouna. “There may have been many Moors in the region at that time. You can find this instrument in the desert in Mauritania or Algeria, not among the Fulani."

Mistakes are often made, according to Alter Natives director Emmanuelle Cadet, who is also at our meeting. Schœlcher, like many collectors of African objects, must have misinterpreted what he was told. And so, for 175 years, the instrument has been presented under a false identity. "It's not the first time we've been told, when showing these objects, that the information collected is not right," she says. “At the Musée du quai Branly [on African and oriental art], there is much work to do on the collections. Just showing these objects to the communities from which they came can cause a whole section of our museums' so-called knowledge to collapse."

The Fulani musician leafs through a portfolio of musical instruments, brought by Issa and Emmanuelle. We ask him about the need to return these objects. “Yes, it is important that they come back here so that the descendants know how their ancestors made the instruments,” replies this guardian of tradition. Haruna then takes a photo out of his wallet. It is his great-grandfather, he explains, a Fulani chief who fought against the French troops of Louis Faidherbe in the 1850s, alongside the famous warlord El Hadj Oumar Tall. A sabre said to have belonged to Tall was the object in November 2019 of the one and only restitution to Senegal by France so far. "The sword returned to Senegal, that's good, but if we go through Faidherbe's belongings we will also find my great-grandfather's belongings," says Haruna.

Far from the communities concerned

There are indeed tens of thousands of objects stored in French and European museums that come from thefts and war captures, according to a report by Senegalese scholar Felwine Sarr and French scholar Bénédicte Savoy commissioned by French President Emmanuel Macron and published in late 2018. But apart from the sword returned to Senegal and 26 royal pieces handed over to Benin, Macron’s promise in his shock Ouagadougou speech to organize "within five years temporary or definitive restitutions of African cultural heritage in Africa" is slow to materialize. It is true that a special commission has been created in Senegal, and that "provenance research" has been launched at the Quai Branly museum in Paris, which alone contains 70,000 pieces from Africa, but Haruna's great-grandfather's belongings are not about to be returned to him. And in Senegal, voices are denouncing the lack of consultation with the people concerned.

Storyteller, teacher and researcher Massamba Gueye greets us in a working-class suburb of Dakar at the Maison de l'oralité et du patrimoine Kër Leyti, which he founded. It is an artists' residence and a place of education for the local youth. He thinks that in terms of restitution almost nothing has been done and mistakes have already been made, as the return of objects can be "more vexing than their departure". "Bringing back the sword without a speech praising his valour is telling us that El Hadj Oumar lost it on a battlefield. Especially since the nearby museum [Museum of Black Civilizations in Dakar where the sword is exhibited] has his shoes, which were left behind. In our country, losing your shoes on a battlefield means running away.”

Gueye thinks attention should be paid to the intangible heritage of which the African continent has been deprived. "Not only is the humiliation far from being healed, but restitution is far from being real," says this man who is also the culture and heritage advisor to Senegal’s President. In Africa, it is the intellectuals who stand up and speak out for restitution, he says, "but these intellectuals do not represent the communities. There has been not a single move to go to the communities that own the property and ask them: what do you want us to do with what we have taken from you? In Senegal there is no such thing. I travel a lot, I am not aware that this exists in Benin, Ivory Coast or anywhere”.

The lack of consultation is general on the African continent, confirms Fatima Fall, director in Saint-Louis of the Research and Documentation Centre of Senegal and president of the International Council of Museums. "In Senegal we nevertheless did it well to get thiébou dieun, the Senegalese national dish, accepted as intangible cultural heritage of humanity. The Senegalese were consulted and strongly approved," she exclaims. "We need to make an inventory, to visit the collections in Europe, and it is partly the role of academics and experts of the Special Commission created in Senegal. But it is not us who can give meaning to these objects, really. We have to go to the people."

“There are two important things to do," says Gueye. “Bringing back the objects symbolically with an apology is a matter of pride. But at the same time, we need to do some digging on the ground here so that when these things arrive, they make sense. It will be useless to bring back objects that we don’t know how to interpret because those who have the knowledge have disappeared. The people are not informed about this debate. They have not even been asked if they want the objects to come back. But they must come back."