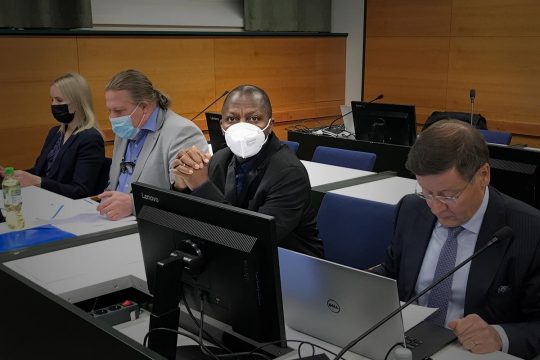

On January 24, 2022, between two hearings, Gibril Massaquoi agreed to speak to us in the presence of his lawyer, in a small room of the court in Tempere, southern Finland. It is the last day of his trial. The former Sierra Leonean rebel of the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) was arrested in March 2020 in this host country, where he was granted a residence permit in reward for his loyal service to the Special Court for Sierra Leone. From 2002 to 2008, Massaquoi served as a key informant for the office of the prosecutor of this UN tribunal, whose mandate was to try those most responsible for crimes committed during the ten-year Sierra Leonean civil war from 1991 to 2001. By providing incriminating testimony, helping to get some of his former comrades-in-arms arrested and recruiting other RUF turncoats, Massaquoi probably escaped prosecution at the tribunal. In exchange for his services, he was relocated and granted exile in Finland with his family.

Since his arrest in Tempere, Massaquoi has been kept in pre-trial detention. He describes particularly strict prison conditions, alone in his cell 23 hours a day, without access to the Internet. For a long time, his visits were monitored by the police, but then they were stopped because of the Covid-19 pandemic. Yet neither he nor his lawyer ever asked for his release before trial. The defence did not want to run any risk of being suspected of contacts or threats against witnesses in the case. Massaquoi apparently put up with his prison conditions with the endurance of one who has seen it all. His only complaint is that his eyesight has deteriorated as a result of living in a cell.

“I have nothing to worry about”

At the end of the war in Sierra Leone, Massaquoi was jailed for a year and a half in Pademba Road prison in Freetown, famous for its terrible conditions. “You can’t compare here to a Sierra Leone prison,” he stresses.

He recounts how he slept well the night after his arrest. The police had told him he was accused of crimes committed in Liberia, a neighbouring country of Sierra Leone, and that was enough to reassure him. “The police said they were surprised. With the kind of charges they’ve put on me it would seem I would be crying in the cell or sitting down lonely and meditating. I went and slept very well because I told them I am innocent, I have nothing to worry about.” His fate is now in the hands of the judges.

“I don’t have my own way. I’m a prisoner. I will go by their decision, whatever the decision.”

Three weeks after this interview Massaquoi, accused of crimes against humanity and war crimes that he allegedly perpetrated in Liberia between 1999 and 2003, can perhaps start thinking he was right to have confidence. On Wednesday February 16, the Finnish judges trying him decided to release him. An hour later, he was freed from jail. The judges gave no indication in their order as to the meaning of this release, only a few weeks before pronouncing their verdict (expected no later than April 29). But speculation has been rife and many observers of the trial see it as a sign of likely acquittal.

Sign of imminent acquittal?

"It's not completely unusual" for an accused to be released at such a stage of the proceedings, says Kimmo Nuotio, professor of criminal law at the University of Helsinki. “The crucial wording is that it would not be reasonable to keep him in jail. In an ordinary case of murder or grave crimes, the first instance court would continue the detention if it has decided to convict. If [Massaquoi] was convicted, the sentence would be much more than two years. It wouldn’t be a problem to continue the detention. This is a bit of speculation because [in its decision] the court doesn’t deal with the merits of the case. But my personal analysis is that there is a slight indication that he is not going to be convicted.”

The day after his release, Massaquoi visited his defence team at the office of his lawyer, Kaarle Gummerus. Massaquoi would not comment. And his lawyer is understandably very cautious. “We asked that if the court finds it unfair to keep him, they should release him” before the verdict, he says, although this was not a formal request for release. “The court, in this situation, thinks it is unfair. Sometimes it means not guilty; sometimes it doesn’t. This is a strange case anyway. But of course, it was good for us,” replies Gummerus, who is clearly in a good mood.

Massaquoi's defence has never flirted with the idea of a strategy challenging the system that is trying him. “I am a permanent citizen of Finland and so even though I don’t understand the law they have a right to try me if somebody says I have killed people in another country. Every European country can do that – it’s not only Finland,” Massaquoi tells us in the interview. “I believe in the Finnish judicial system. I think they will go through the evidence and see. I only have doubt in one person and his team and that is Thomas Elfgren. I don’t trust them.”

The role of Thomas Elfgren

Thomas Elfgren is the police officer who led the investigation in this case. More than that, he has been the lynchpin and mastermind of the trial in its logistics, negotiations with the authorities, media relations and behind the scenes hearings. His role and influence in the process is probably unthinkable in other judicial systems or circumstances than this case in Finland. In Massaquoi's eyes, he and his team are primarily responsible for his plight and the unfairness that he denounces. When asked which three moments from the trial he will remember, the first that immediately comes to mind is: “Thomas Elfgren rushing to me after I sacked my lawyer, to ask me why I sacked the lawyer that he has given to me. He went beyond the boundary. He has no right to question why I changed their own lawyer they had given to me.” The second moment arises from the first. “He did everything to win the case. He's going to retire this year or next, so he wanted to retire with a gold medal," says the accused.

Massaquoi takes time to come up with the third moment he will remember from his trial. “Any good moment?” we ask. Combative, even quarrelsome, Massaquoi remembers times when he was "happy" and "laughed”. These were the times when witnesses alleging to have seen him committing atrocities in the Liberian capital Monrovia changed their testimony in court. “There are not stories of theirs, there have played those stories into their mouth to say it,” he claims.

He thinks this trial has not been fair. “It has not been fair because of the way the police and the prosecutors have been dealing with it. After their first batch of witnesses, they went for a second batch of witnesses, then to a third batch,” he says. “They have amended the charges. I told my lawyers: they want to win the case by whatever means. The only time I was moved during the trial was when the prosecutor sent me new charges in July. I was a bit moved. This is [when I thought]: they want to win this case by force, even when they don’t have evidence. That whole day I couldn’t eat.”

At the hearings, the investigations conducted by the Finnish police were never questioned. When concerns were raised about the collection of evidence, they always targeted the Global Justice Research Project (GJRP), a Liberian NGO and partner of the Swiss NGO Civitas Maxima, the two organizations which filed the complaint that brought Massaquoi to trial. The man the defence has consistently accused is one of the GJRP investigators whom the Finnish police recruited to their investigation team. Massaquoi is quick to point out his enemy. "In Liberia, the [Finnish] police did not do their job as police officers,” he says.

"There have been killings that I participated in”

Since 2003 when we interviewed him in Freetown as he secretly began to betray his former friends, Massaquoi does not seem to have changed either physically, in his quick temperament or in his unshakeable conviction that he is blameless. He was a notorious commander in the RUF and later its spokesman. That movement has been accused of the worst atrocities in Sierra Leone. He was a member of a short-lived but particularly bloody military junta in his country. In 2004, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in Sierra Leone accused him of numerous summary executions within the rebellion in 1993, and highlighted his duplicity in the rebellion's hostage taking of hundreds of UN soldiers in 2000. Both this commission and several members of the UN Special Court’s office of the prosecutor deplored his lack of honesty about his real responsibilities in RUF crimes. In short, they said, Massaquoi got off lightly considering his role and responsibilities in a rebel movement that left the people of Sierra Leone with little more than a litany of atrocities and destruction.

“I read the TRC report, everything. In the initial stage of the RUF there were killings I participated in. And the reasons I stated to the Special Court,” he told Justice Info. These executions, he said, were targeted at Liberian members of the rebellion, who had formed the vanguard at the beginning of the fighting. “They came from Liberia, they killed our people. And they started killing those they had trained as junior commandos. I told the TRC I was part and parcel of it!” But he denies being the one responsible, as alleged in the TRC report. “It was a group of commanders from Pujehun district and I was one of them. It was the only thing we could do to remove the pressure on us. Beside that nobody in Sierra Leone will tell you ‘I saw Gibril Massaquoi killing anybody’”.

Massaquoi is like that. “I don’t regret anything that I have done,” he says. “I don’t regret being a member of the RUF. I don’t regret anything in my life. I regret what the RUF did”, but not to have been one of its highest-ranking officials despite being well aware of the atrocities that his movement was committing.

Nice fat compensation?

One consequence of an acquittal in this already upside down trial would be the financial benefit that Massaquoi would receive. Compensation for the number of days spent in prison is provided for by Finnish law. Gummerus says this represents at least 100 euros per day of incarceration but that in this case, "it would of course be more", given the length of his detention, the rigour of his isolation and the national and international media coverage of the case. Such compensation, explains Professor Nuotio, is “a regular thing in Finland. It’s part of the rule of law. In this case it would be a pretty sum”.

Massaquoi did not want to say in our interview what he would do if he were acquitted. He is in his 50s and is already a grandfather. His children are well settled in Finland. Sierra Leone, for them, has become a rather foreign land. They have never been back. Would he consider returning to his native country? “If I am free maybe I will visit my mother” who lives in Bo, Sierra Leone’s second biggest city, he says. He says he would not have any fears. Would he also go to Liberia? “To Liberia?” he asks. “What would I go and do in Liberia?”