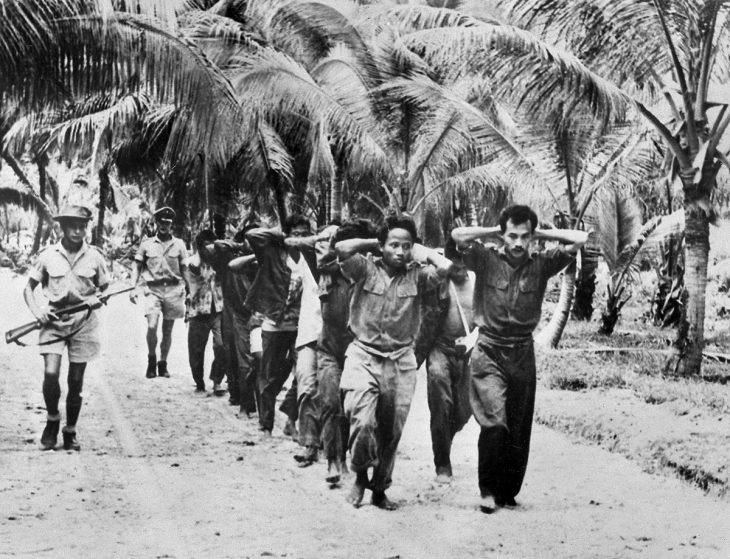

“There’s a line attributed to the German poet Heinrich Heine: ‘When the world ends, then I'll go to the Netherlands, because everything happens there fifty years later’.” Indonesian historian Joss Wibisono notes its applicability to the 70 years it has taken since the end of the colonial war, after a distressing report released last week, to acknowledge that “the use of extreme violence by the Dutch armed forces was not only widespread but often deliberate, too,” and that “It was condoned at every level: political, military and legal”.

In the report, commissioned by the Dutch state from several Dutch researchers who collaborated with Indonesian colleagues, many details emerged of what the soldiers had done to prevent the colony from achieving independence after the Second World War. “What we see over the past 70-75 years is a constantly reappearing of this information,” says Remco Raben, one of the researchers, from the University of Amsterdam. “And constantly, a government that has been able to avoid taking responsibility for what happened”.

Notably in the 1960’s a government inquiry had declared that while excesses had taken place, the military as a whole had behaved correctly. “The government was able to shove it under the carpet” says Raben.

Politicians encouraged the violence

The official government position, held since a 1969 government report into the military’s behaviour, that “regrettable excesses had occurred but the armed forces as a whole in Indonesia and acted correctly (…) is no longer tenable”, says Ben Schoenmaker, director of the Netherlands Institute for Military History at a press conference, held on Thursday 17 February to summarise the findings of the new report. On the contrary, he adds “during the war, the Dutch armed forces used excessive extreme violence in a structural way… violence occurred frequently and was widespread”. And in addition, “the politicians responsible, as well as the military, civil and judicial authorities, tolerated or condoned this violence. They encouraged it. They concealed it, and they did not punish it”.

“There was a collective willingness to condone, justify and conceal it, and to let it go unpunished. All of this happened with a view to the higher goal: That of winning the war”, notes the report. And the researchers found the army “frequently and structurally” guilty of “extrajudicial executions, ill-treatment and torture, detention under inhumane conditions, the torching of houses and villages, the theft and destruction of property and food supplies, disproportionate air raids and artillery shelling, and what were often random mass arrests and mass internment.”

A “very important” pressure to re-examine what had happened, described by the researchers, came with the case brought by Jeffry Pondaag through the Dutch courts on behalf of Indonesian widows who survived a massacre, resulting in damages paid by the state in 2011. Several years later the government agreed to fund this extensive research, which will be published this year in 14 volumes, following the release of this synthesis report. It was conducted by the Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies (KITLV), the Netherlands Institute of Military History and the Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies (NIOD).

“The research shows that the vast majority of those who bore responsibility on the Dutch side – politicians, officers, civil servants, judges and others – had or could have had knowledge of the systematic use of extreme violence,” points out Raben. The military defined the narrative. “The civil authorities in Indonesia, and in the Netherlands, were completely dependent on the military as a source of information,” he says. “They list, they do a body count. That's reported in fairly euphemistic terms. And then moving upwards on the on the hierarchy of the military, this message becomes more abstract and more manipulated”. Nevertheless, “there are people who sent this information about atrocities, et cetera, to the Netherlands and in particularly in the course of the war, people knew.”

Extreme violence, not war crimes

The terminology used by the researchers has come under scrutiny. After the 1960’s adoption of “excesses’, more recently in 2020 the Dutch king, Willem-Alexander, apologised when visiting Indonesia for the “excessive violence” inflicted during colonial rule. Now it is the term ‘extreme violence’ that is used, which Gert Oostindie director of KITLV explained was “an overarching term for really a whole range of different forms of violence,” at the press conference. “It's a broad umbrella concept, but also it has no strict legal connotations,” he said, which left some like Wibisono to think “it's a euphemism”.

While he understands the researchers’ arguments he notes that the report “stops short of using the word war crimes” which would be clearer to the Indonesian public. Raben himself admits he “struggled” with the term extreme violence, because he wanted instead to foreground the actual experience of Indonesians. He notes that “the military and with them the civil authorities in the colony and in the Netherlands have been able to isolate certain events as possible war crimes. They're called the excesses. That is part of the politics of manipulating information”.

Apologies to “all those affected”

In response to the report The Netherlands’ Prime Minister Mark Rutte apologised on the same day, not only for the atrocities committed at the time, but for the failure of past Dutch governments to acknowledge it.

“For the systematic and widespread extreme violence from the Dutch side in those years and the consistent looking the other way by previous governments, I apologise deeply to the people of Indonesia,” says Rutte, saying the government takes full responsibility for the “collective failure”. But the apology is addressed to “all those affected”, including the Dutch forces.

Raben was disappointed: “He apologised to everybody who was around at that time. That didn't give me much hope.” And Wibisono “doubt it very much that it's going to be a step towards, you know, making the perpetrators accountable for what they did.”

“It's another cover up. That's what I'm afraid of.” “I was just surprised that it takes 70 years for the Dutch to come to terms with what they did in Indonesia”, says Wibisono, who is based in Amsterdam and follows Dutch politics.

Controversial History

The end of the colonisation is a period of history that remains raw to many in the Netherlands. One of the controversies has been around what’s known as the bersiap [be prepared] period – a Dutch term drawn from Indonesian to describe the violence committed by independence activists during the 1940’s against the Indonesians who were seen as part of the colonial infrastructure. That violence was used as the justification for the Dutch reoccupation war.

But in the report researchers show that the decision to intervene was not a response to violence. “That decision have been made much earlier” said Oostindie. They also downgraded estimates of how many had died in that ‘bersiap’ violence. “Here's a maximum of six thousand victims, that's a lot of victims” stressed Oostindie, “it is very painful, but it's not the 20 or 30 thousand that you also hear mentioned sometimes”. Earlier researchers had extrapolated that higher number from incomplete sources. In terms of the total numbers of those who died the researchers say the generally-accepted figure of 100,000 Indonesian casualties “is surrounded by much uncertainty”, but “it is absolutely clear that the casualty ratio in the fighting … was extremely unequal.”

Oostindie acknowledged the difficulty many Dutch people would have in hearing the specifics of what their colonial army had done in the 1940’s, “the Dutch politicians and a Dutch society as a whole [have] found it very difficult to move away from the very rosy picture of itself. That rosy idea of the self, that we simply don't do that kind of thing”.