JUSTICE INFO IN-DEPTH INTERVIEWS

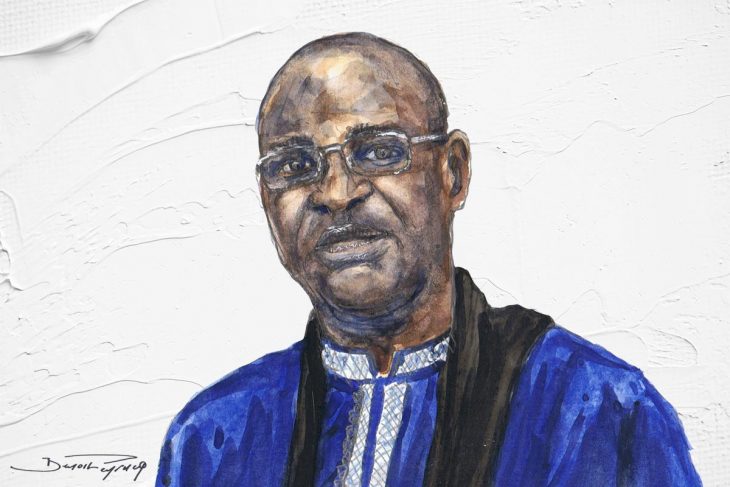

Massamba Gueye

Director of the Kër Leyti House of Orality and Heritage

"I have no master," claims storyteller and teacher Massamba Gueye. He is proud to be part of a generation that went to university in Senegal rather than being educated in the West. This is also true for President Macky Sall, whom he advises on issues of culture and heritage. “We must return everything without negotiating,” Gueye insists. He says a Truth Commission is needed between Africa and Europe in order to realize this dream of a continent at peace.

JUSTICE INFO: France has made a symbolic first restitution to Senegal by returning the sword of El Hadj Omar at the end of 2019. How do you think this was perceived by the Senegalese?

MASSAMBA GUEYE: From a moral and human rights perspective, colonial acts are acts of violence. Based on this principle, there is nothing more unjust than to take cultural objects from a place and turn them into objects with only a narrative function. When you take spiritual instruments from a place and put them in European museums, you kill what I call their socialization function to make them carriers of a narrative. But these are not authentic narratives; they are the stories of their journey. To take a Ntomo Bambara mask and exhibit it at the Museum of Ethnography in Geneva is to kill a whole social function of a certain community and to make a society orphan of its spirituality. So as well as bringing back the physical objects, there is also the issue of reparation for cultural and moral damage. I think we need to approach the question from this angle.

Returning the sword of El Hadj Omar, yes why not. It is an object coming home. But we must first be told how it left, because otherwise it means we are bringing back the symbol of our ancestor’s defeat. Yet in all the lessons we have learned here in Senegal since the 1960s, he was never defeated, but mysteriously disappeared in the cliffs of Bandiagara [present-day Mali]. Just the return of this sword can deconstruct the entire imagination of a population that had built pride. That is the sword of Damocles: we bring back objects but these objects come back to pollute a certain representation of events.

We know that these objects were either stolen, captured in raids, or sold by certain greedy people living in Africa. For me, it is this story that we must build around the return of objects, so that their return does not become more vexing than their departure.

When you steal and you are caught, you return. If the owner wants to burn, he burns, if he wants to throw away, he throws away, if he wants to desecrate, he desecrates, if he wants to make sacred again, he does so.

So in some cases restitution is a reminder of humiliation?

Yes, because I think bringing back the sword without a speech praising his valour is telling us that El Hadj Oumar lost it on a battlefield. Before returning the objects, is there a mea culpa somewhere? Did the thieves acknowledge that they stole these objects, and that by stealing these objects they killed communities, they killed life-giving practices? That is where there is a crime. There is a crime because of the spiritual loss, the rupture of an evolution and the impossibility of a transmission of knowledge. And this immaterial knowledge cannot be reinvented. It is a very serious crime and, for me, to collect thousands of objects to bring us two or three, no. And to ask us if we have museums to keep them, no. Where have we seen a thief ask the owner to create the conditions to bring back stolen goods? When you steal and you are caught, you return. If the owner wants to burn, he burns, if he wants to throw away, he throws away, if he wants to desecrate, he desecrates, if he wants to make sacred again, he does so.

There’s something strange that we have not been paying attention to: they [the Europeans] call these objects cultural 'goods'. In 'goods' there is a financial notion - but they are not goods, they are symbols and functions. Imagine that in 2022 a statuette is brought back to Senegal that had a religious function in a community that has now been evangelized or Islamized and that considers these objects to be animist objects. Is a family that formerly held those values ready to be reminded of its animism? There are disputes that can arise. Mandingo objects taken at a time when certain borders did not exist come back to West Africa, for example, which is divided between the Mandingos of Senegal, the Mandingos of Guinea, the Mandingos of Burkina, and the Mandingos of Abidjan. To which country should these objects that belong to a whole cultural community be given? For our cultural communities do not correspond to our administrative borders.

I’ll give you an example. There are cultural objects that have gone and that are linked to the therapy called N'Döep, a therapy among the Lebous in certain villages like mine, which allowed the treatment of the insane. But the religious objects, the pestles, when they are removed from this space they become kitchen objects. Now, each pestle corresponds to a divinity, it is a person’s psychologist, they will speak to it. But today, the village of Koki has become a centre of Islam with an Islamic institute that has 5,000 students - who is going to tell them take back your animist past?

These are the issues that we do not want to raise. France wants to restitute to salve its conscience, for its national good and its relations with Africa, and this can be good. France can delegate whoever it wants to do a report. But this report [by Felwine Sarr and Bénédicte Savoy, commissioned by French President Emmanuel Macron and published in November 2018], done on France's budget and with France's terms of reference, does not commit me as an African. Even if this report is made by respectable people, it does not commit Senegal and does not commit Africa.

Until now, Africa has not built a coherent discourse. It is intellectuals who speak out, but these intellectuals do NOT represent the communities. There has not been a single action taken towards the communities that own these objects.

So, what is the demand of African states on this issue, and why is it so little heard?

This question must be addressed by the African Union, because it concerns the memory of the continent. Everything that concerns slavery must be the affair of the African Union because, when colonization and slavery began, the countries did not exist. The African Union must speak out in a systematic way.

There is an African Union commission that is trying today with some institutions to lay the foundations. But our request has yet to be formulated. We must say very clearly what we want and how we want it to happen, but we must not echo the will of the West, which has its own philosophy and history, which responds to an internal discourse on human rights and also the values of its new generations which are not responsible for certain things but are guardians of a memory. Until now, I see that this is a weakness for Africa, because Africa has not built a coherent discourse. It is intellectuals who speak out, but these intellectuals do NOT represent the communities. There has not been a single action taken towards the communities that own these objects.

Nowhere?

Nowhere. In Senegal there is no such thing. I work a lot on West Africa, I travel a lot, I organize a lot of cultural events and I am not aware that this exists in Benin, in Ivory Coast. Nowhere did we go to the communities to tell them: this is what was taken from you, this is what it has become, what do you want us to do? There was no such consultation. Today, we have an intellectual movement but we do not have a grassroots social movement to claim these objects.

In Senegal, the only official request comes from the very influential Omar family...

Exactly. El Hadj Omar carries the label of a conqueror, but a conqueror for Islam, which is what I call the backbone of Muslim Senegal today. But what was confiscated from Serigne Touba [founder of the Mouride brotherhood] is claimed by his family. What was confiscated from El Hadj Malick [founder of the Tidjanes brotherhood] is also claimed by his family.

We talk about cultural goods but we do not talk about the legal ownership of these men’s possessions. Much has been written. All this must be repatriated to Senegal. Today, it is important to understand that Senegal is not focussing on El Hadj Omar. Senegal is focussing on all the objects that enriched Nantes and enriched the great collectors, including the collection of Léopold Sédar Senghor which is held by a Frenchman and which we cannot even have.

Here we talk in French about the return of cultural goods, but we don't talk about it in Wolof, we don't talk about it in Joola, we don't talk about it in Serer. This means that, for the majority of people who speak these languages, it is a discourse by big intellectuals. We haven't even asked them if they want this cultural property to come back. But it must come back.

Why is this not being done?

Because since the establishment of French schools, the westernized elite has always considered itself more intelligent and more aware of things, and that others should listen to them. We have this complex. The academics, those who went to the top schools, consider that the others have no say in this debate. This is why conferences and debates are held in French or English, but nothing in the national language. The great African intellectuals today are uncultured in their own mother tongue. And since they are uncultured, they do not want to bring the debate to that level. They want to keep the privilege of what I call the exoticism of Western-style discourse, continuing to drown the masses in poverty and ignorance.

The break with the past that we need is not a change of regime, it is in relations with the population and the popular imagination. The country is managed in Western languages, but the real knowledge is in the local languages.

Do you say this to the President of Senegal when you are advising him?

I say it in public, I say it everywhere -- to the president, to the opposition, to the intellectuals. Even though I have a doctorate in literature, I think that we must work to listen to the people, to raise what they want.

We have reproduced the whole pattern of the colonial administrative culture. Politics continues a system that allows it to perpetuate itself. The break with the past that we need is not a change of regime, it is in relations with the population and the popular imagination. The country is managed in Western languages, but the real knowledge is in the local languages.

To come back to restitutions, what purpose do you think they can serve?

For me, it’s a question of justice. We have to return cultural heritage because it belongs to us. Once we have identified that it has been stolen or sold illegally, we must return everything. And we should not be asked if we have a place to keep it or not. It is not the problem of the West.

Today, ethnographic museums cannot continue to exist showing an esoteric Africa to Africans. Ethnographic museums set up during the colonial period must disappear. We must reinvent them.

And afterwards?

Afterwards, what we do with it is up to us. We are adults enough to do what we want with it. If we want to burn it, we'll burn it; if we want to exhibit it in schools or museums, we'll exhibit. But first let's get our things back. It is this paternalism that I have a problem with.

What does the museum in its current form say to the African? It is also a form of continuation of elitism. For example, IFAN [Institut fondamental d'Afrique noire] in Dakar is a colonial invention that continues to convey this same philosophy, what I call African exoticism. And if we go further, IFAN itself includes elements that do not belong to Senegal. It’s the vast majority. So there is also this question of restitution from Senegal to these countries. We must be realistic: as much as Senegal has the right to come and ask France for its goods, Mali has the right to come and ask the Théodore Monod Museum [IFAN] for its things.

Today, ethnographic museums cannot continue to exist showing an esoteric Africa to Africans. This is where I disagree with many intellectuals. Ethnographic museums set up during the colonial period must disappear. We must reinvent them.

We will take everything back without negotiating. It’s imperative.

Today, this reinvention is being carried out in Dakar by the new Museum of Black Civilizations. But hasn't it declared its ambition to receive everything from the so-called ethnographic collections found in Europe... if everything can be taken?

I would not say if. We will take everything back without negotiating. It’s imperative. Africa’s position on this cultural heritage is exactly like Israel’s with regard to Jewish property. Just the same.

But what the Museum of Black Civilizations wants to do today is first and foremost to save what is still in Africa and was not collected. We talk about what is gone, but there is also what remains and is perishing. This museum has an affirmative approach. I am on its board of directors; this museum does not aim just to affirm Senegalese identity but also rethink the way we talk about Africa. For me, it is very useful. It is a museum that will show the human side. Picasso has his place in this museum, and he will soon be exhibited there. We don't need museums that show the characteristics of a people but museums showing that the human being is unique.

I think we need to do two things. Bringing back the objects symbolically with apologies from the world is a question of pride. But at the same time we need to work on investigation, so that when these objects arrive we know about them.

Returning cultural property is saying to the world: you don't have the right to take the objects of a people so your children can go on field trips, take pictures and say ‘Black people are strange’. We are not allowed to take white dolls to put in our museums. We don't have the right. The human is human. It’s the richness of humans that must be shown in the spaces of the museums, not their differences.

I think we need to do two things. Bringing back the objects symbolically with apologies from the world is a question of pride. But at the same time we need to do excavation work on the ground, work on conservation and investigation, so that when these objects arrive we know about them. It is useless to bring back objects that can’t be understood because those who possess the knowledge have disappeared.

What we need with the West for these objects is a truth and reconciliation commission like in South Africa.

Can we talk about reparation for colonial damage or is it something else?

It is more than reparation. No one can quantify today the financial cost and the income these objects have generated in museums in the West. I think what we need with the West for these objects is a truth and reconciliation commission like in South Africa. There is a moment when we have to stop the bleeding, sit down and recognize the wrongs, to say we stop this process and we start again from A to Z. But the cultural and moral damage cannot be quantified, it cannot be monetized.

Who could lead?

It is Africa. It’s the African Union and the European Union that must address this issue. It should not be left to the fluctuating wills of the States but must be handled at the level of the institutions. And the UN must be there to arbitrate. This is my dream and I will continue to speak and train young people to carry this message.

There is a stirring at the level of the African Union. A few weeks ago, the European Union organized a session at the Museum of Black Civilizations in Dakar to harmonize the demand. But it's complicated with politics. A change of government, a coup d'état in a country and everything falls apart.

I think the world has missed a great opportunity to heal its relationships through the restitution of these goods, to heal the wounds born of colonization. I think we have missed a great opportunity to make peace for the world.

Are there political leaders in Africa today who could lead this project, as was the case at the beginning of independence?

Unfortunately, I don’t see today in Africa a great leader of Senghor’s calibre or Gaddafi’s force of character who carries this great vision of how important our heritage is to our existence. We don't have that. I think that political leaders are more concerned with their re-election than with heritage. Even the restitutions, given how long we’ve been talking about them, if the African Union were to be taking it seriously, we would have had a written and signed African request on the table of the United Nations, with clear deadlines and terms of reference.

Yes, there is a lack of political leadership to carry these issues forward. And that is why France, Spain, Portugal can choose what they want to restore. They can choose the African intellectual who should work on this subject. Africa has not yet chosen these people. As soon as France opened the door with the Ouagadougou speech [by President Macron in 2017], the first thing to do was demand that France and other countries recognize colonization as a crime against humanity in a very clear way. Each African country should have listed its property and demanded a deadline for restitution. But we did not do it.

I think the world has missed a great opportunity to heal its relationships through the restitution of these goods, to heal the wounds born of colonization and allow a new generation to have a different kind of relationship. But France is going to be insulted here, ambassadors are going to be sent back, and this is going to reinforce the hatred here and there. I think we have missed a great opportunity to make peace for the world.

Is it too late?

It's not too late. But the sun is setting. If we don't do something concrete in the next two years, I think this page will be turned and taken over by something else.

Interviewed by Franck Petit

Massamba Gueye is a teacher, researcher and founder of the Kër Leyti House of Orality and Heritage in Senegal. He is a writer and storyteller; technical advisor on culture and heritage to the Senegalese President; and national contact person on the 2003 UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Heritage.