In mid February, Colombia’s Special Jurisdiction for Peace announced it will soon open three new macro-cases: its future dossiers will focus on the brunt of crimes committed by former Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) members and by state agents, as well as on how ethnic minorities were targeted during the country’s armed conflict.

With this decision, the special tribunal stemming from the 2016 peace agreement – locally known as the JEP – significantly changed its approach to how it selects its cases, moving from investigating specific crimes and geographic regions to focusing more broadly on an array of behaviours by specific actors.

However, this announcement, explained in part by the slow pace at which its first seven cases have moved, has seen an unprecedented flurry of critiques from victims and human rights groups – especially since these could be the last probes it opens. Although the choosing of cases inevitably fails to satisfy the expectations of all victims – many of whom are advocating for the crime that affected them to be selected – this is perhaps the first time when victims of very diverse likes are questioning the JEP’s methodology and how seriously its justices are taking their observations into account.

The JEP’s change of heart

Over the past four years, the JEP has been working on seven macro-cases. Four of them focus on highly symbolic crimes committed by two different actors: kidnappings and forced recruitment of child soldiers carried out by the FARC, as well as extrajudicial executions and the mass killing of members of the left-wing Patriotic Union party by state agents. Three additional cases are probing multiple crimes committed by different groups in three specific regions of the country.

On February 18, the JEP announced its “unwavering decision” to open three new cases. A first one will focus on other crimes committed by FARC, including sexual violence, forced displacement, forced disappearance, use of landmines and town sieges. A second one will investigate crimes carried out by Army officials, policemen and other state agents, with an emphasis on sexual violence, torture, land dispossession and massacres, including those in collusion with right-wing paramilitary groups. One last case will examine the suffering of indigenous persons and Afro-Colombians, who jointly account for 10% of Colombia’s population and 18% of its registered victims.

In making this call, the tribunal explained that it already possesses a wealth of information on the armed conflict, after its ‘contextual analysis group’ studied 458 reports submitted by victims’ groups and state agencies, and identified 258.000 criminal offences. Its justices argue that focusing on these other criminal patterns by FARC and state agents makes sense, now that they have built an in-depth understanding on the behaviours of each actor over time and geography.

They also announced a series of public hearings in six cities to gather observations from victims and human rights groups. The last of these ended last Friday in Bogota.

A ticking clock

The JEP has so far taken much care to avoid indicating that choosing these crimes amounts to deciding that it shall not prosecute others later on, but victims and justices alike are aware that this is the likeliest scenario in a country that endured a 52-year-long armed conflict that left 9,2 million victims. Especially since the clock is ticking for the tribunal, which has a 15-year lifespan that admits an additional extension to fulfil residual tasks. In theory, the JEP has until 2028 to present charges against those most responsible for serious crimes and until 2033 to complete the trials.

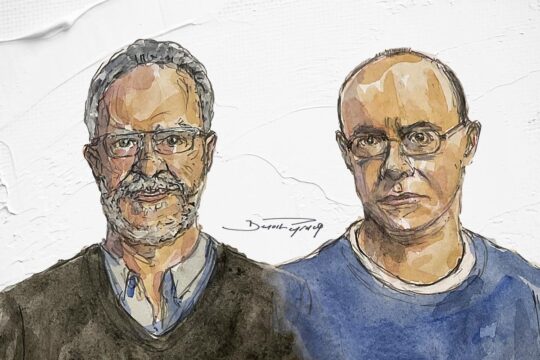

Right after it unveiled its new dossiers, the JEP also announced dates for the public hearings in which its first batch of 17 indictees will accept the charges brought against them. Between March 28 and April 1st, seven former FARC commanders will officially face their victims and own up to their responsibility over thousands of kidnappings. Three weeks later, on April 21 and 22, ten former Army officials will formally admit to their role in murdering 247 civilians and then unlawfully passing them off as rebels killed in combat, a tragedy known as “false positives”.

Their admission paves the way for the JEP to hand down its first convictions since opening its doors in early 2018. They are expected to receive 5-to-8-year sentences in a non-prison setting, provided justices also deem that they’re answering to victims’ demands for truth and redress.

This schedule, however, underscores how long each case is taking. Those first two accusations were unveiled after three and a half years of investigations, with an additional year having been needed to process observations from victims and receiving a formal response from those standing accused. And still a few months more will pass before the JEP’s ruling justices hand down these penalties. This means that at least five years are needed for a ruling, a time span that doesn’t take into account that these first two cases still have other pending indictments against regional FARC commanders and military officers from other prioritised units.

A cause of even greater concern is that the other five cases opened are still in the investigative stages. In theory, the regional case focusing on Nariño on the Pacific coast and the one examining the elimination of the Patriotic Union are nearing the accusation stage, but no official announcements have been made.

Victims (and politicians) push back

The tribunal’s decision to open the new so-called ‘umbrella cases’ has sparked frustration among victims and human rights organisations. Many feel that the six hearings convened by the JEP to discuss case prioritisation were rendered innocuous given that justices had already made their mind up on the upcoming cases. And they’re particularly concerned about what this might leave out.

“We know a prioritisation is needed, but it has to be done in such a way that victims feel included, even if they know that their case will not be prosecuted”, says Adriana Arboleda, a lawyer at the Corporation for Judicial Freedom in Medellín. Her NGO has been calling on the JEP to open a geographical case on the Comuna 13 neighbourhood of Colombia’s second largest city, where – they contend – state agents led by Colombian Army General Mario Montoya disappeared and displaced thousands of persons in cahoots with paramilitaries. Her concern, she says, is that “under time constraints, the JEP might end up sacrificing outreach and participation”.

In February, 85 victims’ and human rights groups penned a public letter asking the JEP to postpone the hearings until the tribunal could address their concerns that the decision process is “hurting the principle of victims being at the centre” of proceedings. Some even went as far as filing legal protection actions against the tribunal in a bid to have their cases considered. As a result of one such suit by an unnamed victim of FARC’s 2003 car bomb inside Bogota’s El Nogal social club, the JEP established a mid-April deadline for its definitive case announcement.

Even politicians are also lobbying the JEP to open other new cases. President Iván Duque, an outspoken critic of the transitional justice system who only visited the JEP’s headquarters in Bogota for the first time last November when the UN secretary general António Guterres came for the peace deal’s fifth anniversary, asked the tribunal whose importance he has constantly downplayed to investigate crimes committed against soldiers and policemen.

Women demand a sexual violence case

Victims of sexual violence have been perhaps the most vocal group in demanding a full case as opposed to being included as part of a broader probe. “The country needs an acknowledgement that this happened. Without such a case, it will be much more difficult to understand how women were seen as spoils of war, how entire territories were occupied through women’s bodies”, says Marina Gallego, leader of the grassroots organization Women’s Route to Peace. Her nationwide victims’ organization submitted a report detailing cases of sexual violence in Urabá to the JEP and is finishing another one in Putumayo.

As JusticeInfo has told, hers and other groups have insisted since three years ago on the need of a case detailing different forms of gender-based violence such as rape, reproductive violence – which includes forced contraception, sterilisations and abortions – and violence against LGBT persons.

What historically was an underreported crime has come to the forefront in the wake of the global reckoning sparked by the #MeToo movement and it has even become a punching bag in the Colombian transition. In total, 34.592 persons have been victims of sexual violence, 90% of whom are women. Although this might seem like a small number amid a universe of 9,2 million victims, the number of persons reporting such cases has grown far quicker than for other crimes over the past seven years.

Indeed, this demand was voiced in every single one of the public hearings convened by the JEP to discuss case prioritisation, according to two persons with direct knowledge. Likewise, it features prominently in the 421 reports submitted to the JEP describing crimes: more than a third – 130 – address sexual and gender-based violence. This only ranks behind homicides, forced displacement, forced disappearance and physical attacks, way more than historically visible crimes like kidnappings or child recruitment, according to an analysis carried out by the tribunal.

Seeking justice for women

Women’s rights groups agree with victims’ concerns. “Our peace agreement was a pioneer in including sexual violence and a gender-based approach. That created a huge expectation among victims, who believe in the transitional justice system and in the possibility of an access to justice they never had”, says Linda Cabrera of Sisma Mujer, one of the oldest feminist organisations in the country. Her organisation, alongside four others, has publicly called on the JEP to open a case covering all forms of gender-related violence and unsuccessfully lobbied International Criminal Court prosecutor Karim Khan to persuade the JEP into doing so.

One of their arguments is that the ordinary criminal justice system is long indebted to survivors of sexual violence. Out of 634 cases prioritised by two Constitutional Court edicts, only 14 – or 2,2% – had seen a conviction, according to a 2016 report by 12 legal and women’s rights NGOs. Impunity levels in prioritised sexual assault cases ranges between 92% and 97%, they concluded.

“We’re not seeing a gender-based approach in the JEP’s methodology. Our experience is that when serious human rights violations are investigated simultaneously, there is a risk that sexual violence is rendered invisible or left aside. It’s part of what has happened in Colombian judicial history”, says Cabrera.

Landmine victims also feel left out

Victims of other highly symbolic crimes are also raising their voice in a country that has one the highest tallies of displaced persons and landmine victims in the world.

“The JEP has the tools to make those responsible admit to their use of landmines and tell us truths like who buried them, how they chose where to do so and how they made them”, says Reinel Barbosa, a 36-year-old farmer and IT technician who lost his left leg after stepping on a landmine in 2007. Since then, he has become one of the most vocal leaders of one of the least visible group of victims in the country, founding the first nationwide network of landmine victim associations and long advocating for humanitarian demining efforts.

A case on landmines makes sense in a country with 12,036 direct victims, without counting relatives. Much of this responsibility lies with FARC, which the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL) described as “probably the most prolific user of antipersonnel mines among rebel groups anywhere in the world”, although the ELN guerrilla and right-wing paramilitaries resorted to them too. It’s also a crime in which the ordinary criminal justice system hasn’t made much headway, with the first such conviction ever – of a FARC rebel – only occurring in 2015. The Colombian Campaign to Ban Landmines, the ICBL’s national branch and the NGO which promoted its inclusion in the criminal code, doesn’t have records of any other conviction.

The problem, Barbosa says, is that most landmine victims do not know for sure who installed them, given that these contraptions often explode years – or even decades – after being buried.

“In my case, it’s been 14 years without an identification of who was responsible”, he says. But, with the information the JEP has already gathered on which FARC units operated in different areas and time periods, he believes it would be possible to pinpoint responsible commanders.

The tribunal is considering including landmine use within the FARC macro-case, as part of an investigation line on ‘means and methods of war’, alongside town sieges and car bombs. Barbosa says he’s not fixated on landmine use as a case on its own, but warns that the priority for victims is to see perpetrators held accountable for a war tactic that targeted civilians and that was often connected to other crimes like forced displacement and confinement.

Bringing back victims at the centre

Although they understand the JEP’s time constraints, in demanding that the crimes they suffered are investigated, victims are also advocating for the narrative focus to return to the victims, rather than the perpetrators.

“The language of war tends to shift the blame to victims. People speak about ‘landmine accidents’, as if these were self-inflicted, when in reality they were minutely planned attacks. We need to call things by their name and seeing those who planted them own up to it achieves that”, says Reinel Barbosa. They’re also pressuring the JEP to open broader spaces of dialogue with victims to discuss case prioritisation. As Linda Cabrera says, “they owe the women’s movement a clear explanation for the postponement and eventual decision of not opening a case, if that is their position”