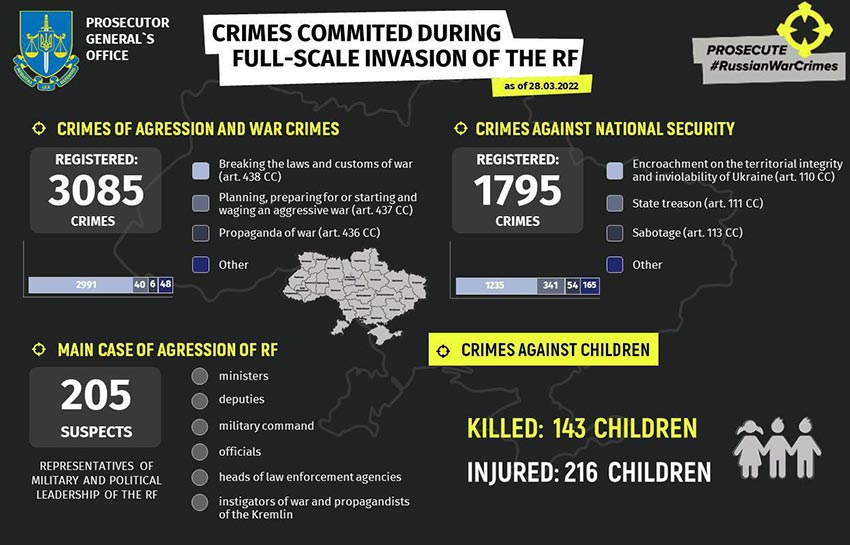

Law enforcement agencies of Ukraine did not need to ‘spring into action’ in the wake of Russia’s invasion on 24 February 2022: it had already accumulated the experience and know-how of investigating and prosecuting conflict-related crimes in its territory over the preceding eight years. Ukraine’s General Prosecutor’s Office (GPO) has set up an online portal to be used for submitting the information about most recent alleged crimes. As of 28 March 2022, it has registered 3,085 crimes involving at least 205 suspects from among Russian ministers, parliamentarians, army high command, state officials, law-enforcement officers, and most notorious Kremlin propagandists.

Abhorrent images and footages recorded by the authorities, civil society actors, reporters, and eyewitnesses on the ground and circulating widely on the social media attest to an unimaginable scale of destruction and human suffering. The ‘blitzkrieg’ has now exceeded tenfold the time its authors thought the installation of a puppet government in Kyiv would take. As the hostilities became protracted, the Russian armed forces turned to the military tactics tested and tried over two decades ago in Grozny, Chechnya and more recently in Aleppo, Syria: laying siege to strategic towns, systematic shelling by heavy artillery of civilian objects and infrastructure (hospitals, schools, and makeshift shelters) and deliberate targeting of ambulances, rescuers, and journalists in ‘double tap’ strikes. The use of imprecise weapons such as unguided missiles, cluster munitions and, as alleged most recently, phosphorus bombs or incendiary submunitions, in urban settings has reduced the suburbs and residential neighborhoods in Kyiv, Kharkiv, Chernihiv, Mariupol, Volnovakha, Irpin, Mykolaiv, and countless other cities and towns to rubble. The death toll among civilians is on the rise. The besieged Mariupol has been described as a ‘hell on Earth’. Over three million of Ukrainians became refugees elsewhere and this number will grow exponentially.

Ukraine takes centre-stage

Ukraine’s judiciary intends to investigate violations of the laws and customs of war, planning, preparing or unleashing, and waging an aggressive war, and incitement to war. Via her social media, the Prosecutor-General Iryna Venediktova has highlighted the ongoing investigations into the forcible transfer, under the guise of evacuation, of the Ukrainian civilian population including children from the partly occupied Mariupol, the use of civilians as human shields, and the causing of environmental damage.

As the territorial state, Ukraine is best placed to carry out investigations and prosecutions in the cases involving low- and mid-level perpetrators on the ground, insofar as it has access to crime scenes, evidence, and suspects it can apprehend. Some evidence will be located outside of its borders but can be obtained in due course by directly interviewing witnesses from among the refugees or through mutual legal assistance.

Although any evidence and suspects located in Russia remain out of reach for the time being, Ukraine can count on evidentiary and operational support by a growing number of other states. Russia’s aggression has triggered a uniformly strong reaction in the capitals across Europe and beyond. Projections of individual responsibility for conflict-related crimes have been part and parcel of that response from the start and have galvanized practical measures undertaken by states on multiple fronts.

National investigations in Europe and beyond

The prosecution services in at least eleven other European states—Estonia, France, Latvia, Lithuania, Germany, Norway, Poland, Slovakia, Spain, Switzerland and Sweden—have announced investigations into war crimes and crimes against humanity in Ukraine based on the principle of universal jurisdiction. The list of these countries will grow and soon encompass not only most of the European Union and associated states but also spill over beyond Europe. As the Ukrainian refugees and, at some point, potential suspects from among the former Kremlin functionaries and Russian servicemen settle down elsewhere (think of former USSR states in the Caucasus and Central Asia, Turkey, Israel, US, and Canada), those receiving states may also be prodded to experiment with universal jurisdiction prosecutions of the Ukrainian conflict-related cases — the political will, legislative arrangements, and prosecutorial ingenuity and resources permitting.

In case of Poland, the current investigation covers the crime of initiation or waging of a war of aggression and war crimes. Rather than looking into specific reported incidents and individuals, Swedish, German and Spanish prosecutors have announced structural investigations into the serious violations of international law in Ukraine. Those do not target specific persons from the outset but are meant to gather evidence in relation to the conflict generally. Thus, the investigators can construct a solid evidentiary foundation to anticipate—and pro-actively build—cases for the benefit of future criminal proceedings in domestic, foreign, or international courts, such as the International Criminal Court (ICC). The states in the business of structural investigations have been able to quickly step up to the plate and capitalize on their recent experience of carrying out similar investigations and providing legal assistance in connection with cases involving former members of the Syrian regime, ISIS/Da’esh and other categories of perpetrators.

States with high intelligence capacity, including non-parties to the ICC Statute ready to support the ongoing accountability efforts, could play a vital role in helping build cases and have some of the suspects arrested in due course. The US State Department has already qualified the conduct of Russia’s forces in Ukraine as war crimes and pledged to keep tracking reports and “pursu[e] accountability using every tool available”.

The unprecedented support for the ICC

Many more states have quickly expressed their commitment to criminal accountability through showing support to the ICC. By now 41 States Parties to the Rome Statute – the founding treaty of the ICC – have referred the situation in Ukraine to the ICC Prosecutor. Such express and wide state support for an ICC investigation is unprecedented, and this time it is more than a symbolic gesture: states have proved eager to commit funds and second national personnel the ICC Prosecutor asked for in his repeated calls for assistance.

Lithuania—the first State Party to refer Ukraine—also became the first to declare its intention to allocate funds (€100,000) to support the ICC probe. Several states followed suit soon enough. The UK will donate an additional £1 million and provide military experts in intelligence-gathering. It will also task the war crimes team in the Metropolitan Police’s Counter-Terrorism Command with bolstering the ICC efforts. France has announced that it will second magistrates, investigators and experts to the ICC and commit an initial amount of €500,000. Time will tell how many (and how soon) other State Parties will put their money where their mouth is and alleviate the ICC’s resource constraints in tangible ways.

Focus on and strengthen existing mechanisms

The plurality of initiatives to bring the authors of core crimes in Ukraine to justice raises not only the familiar operational questions but also the more fundamental dilemmas of prioritization and coordination among the extant (and any future) accountability avenues with a view to maximizing their overall effectiveness. In an emerging multipolar, multi-tiered and highly dynamic accountability landscape, the success of their shared mission will depend on whether states, international organisations, and advocacy groups will set the right priorities and pursue them in a principled and dogged manner. Moreover, the quality of cooperation between different accountability actors, the degree of interlacing and cross-pollination among the parallel efforts will prove the key determinants of success. They will need to use the full potential of existing mechanisms of cooperation in international crimes cases combined with novel and creative approaches.

In terms of prioritization, the issue of a separate international (super ad hoc) aggression tribunal for Ukraine has been widely debated. So much so that it has become something of a red herring in the ongoing road-mapping exercises, even though both the legitimacy and expediency of this option are bound to be questioned. As noted elsewhere, before we venture and invest in a wholly new institution and spread the already limited resources and political attention span even thinner, the option of strengthening the current international and domestic accountability mechanisms must be preferred instead.

Much attention has been—and continues to be—paid to the ICC’s role in advancing accountability. Its investigative team has been working in the region since early March 2022, and the OTP operates a secure portal through which anyone can contact and provide relevant information to ICC investigators. The ICC Prosecutor undertook a visit to Poland and Ukraine. The presence of his Office in the region and the flurry of activity backed by extraordinary multilateral support cannot but create expectations on the part of Ukrainian citizens and government.

One should be careful, however, not to oversell the ICC as the prime accountability avenue. Even with the benefit of seconded staff and extrabudgetary contributions, completing investigations in the fog of war and building credible trial-ready cases will take more time and effort than may be desirable. In its investigation, the ICC Office of the Prosecutor will rely on the information and leads provided by the partners, not least the Ukrainian authorities. In honoring the complementarity principle, it should refrain from taking on cases that Ukraine or other jurisdictions are willing and able to deal with themselves. Instead, the ICC Prosecutor should rather focus on figures from the top political and military echelons of Russia and confidentially seek (sealed) arrest warrants for the time when executing them becomes a possibility.

‘Solidarity justice’

The fact remains that (much of) the future of international criminal law is domestic – and Ukraine is no exception. The accountability record in this situation will consist mostly of cases prosecuted in Ukraine and in other countries where victims and perpetrators will find themselves in the coming years. This is not just new wine in old skins. The situation in Ukraine will become the breeding ground for innovating forms of international cooperation in war crimes cases – a coordination framework that can be called ‘solidarity justice’.

A broader ‘justice coalition’ of states is being forged to work in concert with partner organisations such as the ICC and Eurojust. The coalition members will not only coordinate their investigative activities, but they will operate together through joint investigative teams. On 25 March 2022, the chief prosecutors of Ukraine, Lithuania and Poland and their Eurojust representatives signed an agreement establishing a joint investigative team (JIT) to collect evidence relating to Russia's aggression and war crimes in Ukraine (‘Lublin Justice Triangle’). Although Ukraine is not (yet) a member of the European Union, it has an Agreement with and a Liaison Prosecutor at Eurojust. It has also been involved in the recent consultations within its Genocide Network. Eurojust has been assigned a key coordinating role in part of European Union and partner states’ investigations into the core crimes in Ukraine, and such coordination will be done in close cooperation with the ICC. In fact, the first JIT team has been put together with the support of Eurojust and is open for participation to other parties. This modality presents major efficiency gains as evidence can be collected by and on behalf of all members to then be placed at the disposal of the represented forum states and shared with other accountability actors.

The exact contours of accountability solutions for Ukraine await to be delineated and their outcomes are the known unknowns. But what is certain is while Ukraine cannot and will not be left to travel this road alone, in the spirit of ‘solidarity justice’, it will also be firmly at the helm of this quest for accountability.

Sergey Vasiliev is an Associate Professor at the Department of Criminal Law of the Amsterdam Law School, where he teaches international, comparative, transnational and European criminal law. He is also a founding director of the Amsterdam Center for Criminal Justice.