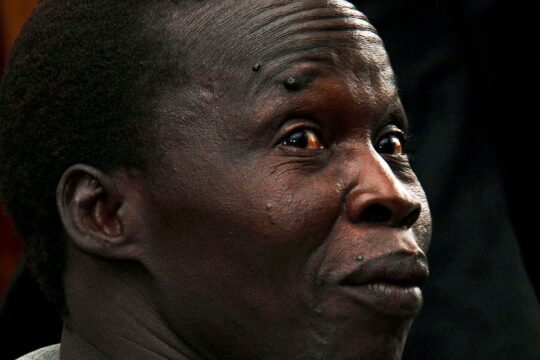

"Everybody is in agreement including the prosecution and court that his case has dragged on for too long,” Thomas Kwoyelo's lead counsel Dalton Opwonya told Justice Info on March 28. “There is no one who has stayed on remand for over thirteen years like Kwoyelo since the time he was put in custody. That is a long time, yet the trial is just starting."

The International Crimes Division of the High Court sitting in Kampala "has planned to have a six month non-stop trial, but government does not have money nor even the time", Opwonya added, so "it has been decided we do two weeks trial every three months, meaning eight weeks a year". The next session of trial will be early May this year.

One of Kwoyelo's relatives who visited him in the high security prison in Kampala recently and preferred not to be named said the former rebel commander complained of high blood pressure and paralysis on the right hand side, a health condition one of his other lawyers, Caleb Alaka, confirmed. "He has serious medical conditions, and he has told the court that he needs to be granted bail to seek treatment outside the prison. But court insists he will receive the treatment in prison," Alaka told Justice Info.

“More hope now than before”

"Justice has to be seen to be done and there is no any other way in this," Alaka said of the sluggish trial. For the state lead counsel in the trial, William Byansi, "the good thing is that all parties in the case have prepared and now the trial has resumed". He added that "the public has to be aware of the complexities of this case".

According to Ugandan judiciary spokesman Jameson Karemani, "the judiciary has tried it's best so far; it provided the Justices to preside over the case and the resources and logistics to facilitate the process". "There is more hope now than before," he noted. When asked about the cost of trial, Karemani referred us to the court Registrar, but attempts to get the figures were yet to bear fruit by the time of filing this report.

Kwoyelo was taken into custody in 2009. He was arrested after sustaining injuries in battle, an episode that ended his 16-year participation in rebel activity. In 2011, the international crimes division of the high court charged him with 93 counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity, including rape, murder and recruitment of child soldiers.

During the hearings in March, Kwoyelo pointed out to court that his LRA colleague Dominic Ongwen, who surrendered to US authorities in 2015 and was subsequently transferred to the International Criminal Court in The Hague, already knows his verdict, whereas he (Kwoyelo) is yet to start the trial phase. The ICC sentenced Ongwen in May 2021 to 25 years in prison, which he has appealed.

"If this court cannot give me a speedy trial, let me be taken to the ICC in The Hague," he told the International Crimes Division of Uganda recently, according to his lawyer Opwonya. But the court said it was only competent to deliver justice to him and the parties in the case.

According to his lawyers, Kwoyelo is also unhappy that the trial is taking place in the capital Kampala, instead of Gulu in northern Uganda, where his relatives could attend. But "we have ensured relatives including his two wives attend court sessions and visit him in prison", Opwonya said.

“Not on government’s priority list”

But Martin Aliker, a veteran researcher and analyst working on peace building programmes in Gulu, says Kwoyelo's case is not on the government's priority list. "Kwoyelo's case has been taken by events. Government's priority is rebuilding northern Uganda and issues that affect the ordinary lives of the people and there is no urgency for call to justice," he said.

"Government has to put its resources to the urgent needs of the people," he continued. "The LRA issue is fizzling out, yet this makes it unfair to Kwoyelo." On Kwoyelo's demand to go to the Hague for trial, Aliker thinks that "when Kwoyelo asks to be taken to ICC, it is not that Kwoyelo believes in his innocence, but that he believes in the voice and opportunities offered by ICC".

After focusing on the length of the proceedings, a dozen prosecution witnesses were presented during the March hearings, out of more than 90 that the state has listed to testify. And as the trial limps on, observers and human rights groups are turning their attention to the merits and demerits of the case.

Kwoyelo was a child at the time he was abducted by Joseph Kony’s LRA, and was conscripted against his will in the rebel group. "Questions still arise as to why of all the senior LRA commanders, some more senior than Kwoyelo, he would be the only one tried and not given amnesty although he applied for it," says human rights advocate Moses Sserwanga. "Wouldn't that be a possible case of double standards?" Since 2000 when the domestic amnesty law was put in place, over 12,900 former LRA combatants have been granted amnesty. There are no others under trial for war crimes and crimes against humanity.

No witness protection program

In a report last year, Human Rights Watch expressed concern at the lack of a witness protection programme. With no witness protection programme in place, witnesses may be exposed, their safety compromised and some traumatised for life, it says. It also says there is no professional interpretation system that can be used during the trial, whereas some local dialects are used. With court relying on various individuals, court staff and even guards, there is a risk of having varying interpretations of what the accused and witnesses say in court, the report stressed.

As Kwoyelo waited years for his trial, public expectations of the case have died down, as have expectations of the country's international crimes division. This institution was established in 2008 to offer an alternative domestic remedy while the ICC launched investigations to establish the highest responsibilities on both sides of the conflict between the Ugandan state and the LRA.

With the first two weeks of daily trial sessions ended, the next session is expected in May.