The defendant and the witness have many things in common. Both are former military officers, both were part of Gambia’s ex-dictator’s notorious death squad known as the “Junglers”, both have claimed that they were present and sitting in the same car during the deadly attacks on a journalist and a lawyer almost twenty years ago. The two men left the Junglers and their country behind at some point, and made their way to Germany. And both of them talked about their past to an oppositional Gambian radio station, revealing the details of the deadly attacks and their role in it. But on this day, in a German courtroom, there is one big difference between Bai Lowe and Sheriff Gisseh: Lowe is accused of crimes against humanity, while his former colleague is a free man, who has been summoned as a witness. The Gambia trial in Celle, Germany, has illustrated once again how fine the line between witness and suspect can be in universal jurisdiction cases.

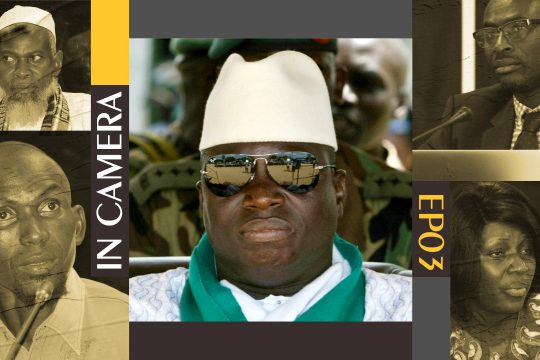

The first trial against a member of ex-dictator Yahya Jammeh’s death squad started in the north-western German city of Celle on the 25th of April. Bai Lowe is accused of crimes against humanity in conjunction with two murders and one attempted murder. Germany is conducting the trial under the principle of universal jurisdiction, that allows states to prosecute the gravest crimes against international law, even when there is no direct link to the prosecuting country. Lowe is alleged to have been a member of the Junglers and to have carried out several of Jammeh’s illegal orders to kill. According to the indictment, “the aim of these operations was to intimidate the Gambian people and suppress the opposition.” One of the victims was journalist Deyda Hydara, whose son Baba Hydara has joined the proceedings as a joint plaintiff. Bai Lowe is not accused of having killed anyone by his own hand, but of being the group’s driver. He allegedly drove the killers to their missions and in one case used the car to block a victim’s vehicle. Among the main evidence against Lowe is is an interview he gave in 2013 to the oppositional US-based Freedom Radio, where he describes being present during the assassinations.

Ex-Jungler remains silent

On Monday, Sheriff Gisseh was summoned by the court to testify. He, too, gave a lengthy radio interview to journalist Pa N’derry Mbai in 2014. There, he mentioned sitting in the car with Lowe, while his colleagues were shooting lawyer Ousman Sillah in December 2003 and journalist Deyda Hydara in 2004. However, when Gisseh appeared in court, he was not willing to repeat that statement. The 50-year-old was accompanied by a lawyer, who apparently had advised him to remain silent in order not to incriminate himself. With Gisseh being an ex-Jungler, the judges in Celle had been ready to inform the witness of his right to remain silent regarding certain information: “He is entitled to an extensive instruction in accordance with paragraph 55 [the paragraph in German law that defines the right to remain silent in order not to self-incriminate]”, said Judge Günther before inviting the witness into the courtroom. But it seemed they had not expected him to refuse to testify altogether – a quite short-notice decision, perhaps taken by Gisseh after consulting with his attorney that morning.

As Gisseh left the courtroom after just a few minutes, he passed by Lowe. The two former colleagues, both in casual sportswear, murmured some unintelligible words to each other. Then, an officer from the German federal police (BKA) was called in to summarize what Gisseh had told him in an interrogation in May 2021: that he and Lowe received military training from Libyan trainers at the end of the 90s; that they were subsequently recruited into the “Patrol Team”, which is known colloquially as the Junglers; that Lowe was the only driver of the team; that he, Gisseh, never killed anyone and always questioned the legality of these missions, which is why he lost his superiors’ trust and left the army in 2005; that Lowe asked him why he left, claiming that “it’s all right and the money is good”; and that Lowe was a “decent, respectful person, a good Muslim, who did not do drugs, drink or smoke”.

Different statements on the radio, to the police and in court

According to the German police officer, however, the witness retracted what he had said on the radio about witnessing the killings of journalist Hydara and lawyer Sillah. With Lowe having been arrested two months prior to his police interrogation, Gisseh might have gotten worried. “He claimed that he had lied in the radio interview to make his statements more credible to the audience”, said the BKA officer in court. Gisseh’s statement on the radio does sound like a first-hand account. He lists the people who were in the car with him – among them Bai Lowe -, what type of car it was, who shot at Hydara and Sillah, and how he heard the victims screaming. But according to the BKA witness, “he said he only heard about the incidents from colleagues and in the media, and that he repeated what Bai Lowe had said in his radio interview.”

He told the German police that he could not have participated in Hydara’s assassination, because he was not asked to join such operations anymore at the time. He said that having lost the trust of his superiors he was only employed in office jobs. And during the attempt on Sillah’s life, he claimed, he had been at his best friend’s wedding. To the defence’s question, whether the federal police had verified this information, the BKA officer responded that they had not conducted any further research into the matter.

He ”just sat in the car”

After all, Gisseh was not questioned as a suspect but as a witness. Federal prosecutor Schmidt confirmed in court that to their understanding of his radio interview, Gisseh had “just sat in the car” and therefore they had had no initial suspicion against him when they summoned him for questioning. However, she added, they had been prepared to change his status from witness to suspect during the interrogation, if relevant information had been provided.

She referred to the case of Eyad Al-Ghareib, the Syrian officer who was sentenced to four and a half years in prison by a German court for aiding and abetting crimes against humanity in Syria. He had started out as a witness to the BKA and became a suspect during his testimony. The prosecution, however, had not noticed until after his interrogation, and so had failed to inform him of his rights as a suspect. This mistake had proven a controversial issue throughout the whole trial and had been one of the crucial lines of Al-Ghareib’s defence. The tightrope walk between witness and suspect might come up more often during universal jurisdiction cases in the future, especially when they rely so heavily on insider witnesses due to the distance in location and often time to the crime scene.