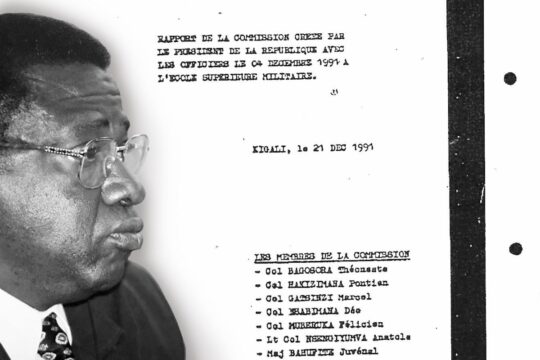

Dark, cold and heavy clouds loom over foggy, grey Brussels. A large crowd stands in line to enter the old Justice Palace, which has been under reconstruction for a couple of years. An elderly Rwandan man, wearing a chic white trench coat, manoeuvres through the scaffolding and smoothly jumps the line. At 71, his pace is slow. He drags one of his feet. Supporting himself with a crutch in his right hand, he passes security and makes his way up the imposing stairway. His destination is a timeworn, dingy and dark courtroom. It is located at the outer wing of the historic Palace, which was inaugurated in 1883 by King Leopold II, infamous for his lethal colonial exploitation of the Congo Free State, today’s Democratic Republic of Congo. Decorated with black, red and white marble and biblical paintings, the large echoing hall is filled with the fatiguing warmth of a central heating system. Once inside, the Rwandan man wipes the fog off his thick black glasses and takes a seat in the dock.

Is a lay jury suitable?

Opposite to Fabien Neretse sit no less than 21 Belgian jurors. In the end, twelve of them are tasked to assess whether the man in front of them is guilty or not of genocide, for crimes committed more than 25 years ago and thousands of kilometres away, in Rwanda. With the decline of international tribunals, national trials claiming universal jurisdiction for international crimes are running the show in Europe. But how are ordinary Belgian citizens to seek, find and establish the truth about the genocide of Rwanda’s Tutsis in 1994 – so unfamiliar to them? Is a lay jury – although the bench is also composed of three professional judges – capable or even suitable to decide?

A loud bell rings in the Palace of Justice, followed by the clerk’s announcement of “La Cour”. It is December 2. Sitting for nearly ten hours on that Monday, the jury hears the stories from six Rwandans, including a former soldier, an evangelist and a driver from Mataba, Neretse’s hometown in north-west Rwanda. Fabien Neretse’s trial at Brussels’ Cour d’Assises has moved into its fifth week and is nearing its end. Closing statements are planned to start the following week. Out of the 106 summoned witnesses a little over fifty Rwandans have already come to Belgium’s capital to testify for or against Neretse. Huge curtains remain closed during hearings in the courtroom, days are short at this time of year and trial participants and jurors end up spending them without seeing daylight. “We are sitting in court from 9 a.m to 7 p.m, then I am writing up my reports until 2 in the night,” says a Rwandan journalist in a lethargic tone. He has followed all trial days since its start on 7 November.

Brussels lottery

Only such a fierce schedule could allow for the trial to last the assigned six weeks and come out with a judgement before Christmas. And so, jurors must dutifully sit for hours on red-cushioned tip-up seats behind a long brown wooden bench. At the end of protracted, intense days of concentration, jurors yawn, eat snacks to get one last sugar rush or stare at the bottles of water and Coca Cola they have consumed in the past hours. One of them, revealing eyes ringed with dark circles under her hijab, sips from a large black coffee mug, hoping to stay clearheaded. When it is already dark outside and the last testimony of the day comes to an end, none of them, nor the parties’ lawyers, seem interested any longer to question a Rwandan farmer from the far away, unknown Mataba commune. It is 6:35 p.m. and the court’s theatre pauses for the night. Sighs of relief from the jurors’ podium are audibly travelling through the courtroom. Some cannot hide a little smile, ready to rush into their coats.

To decide whether Neretse is guilty or innocent, the 12 jurors - accompanied by 9 reserve jurors - were appointed by means of lottery before being sworn in. The requirements were that they had to be registered voters, enjoy civil and political rights, are between 28 and 65 years old, can read and write, and have not been convicted to heavy sentences. In other words, virtually every Belgian could be one of them. Those selected in the Neretse trial are men and women of varying age, ethnicity, religion, social class and style. Dressed casually and armed with coffee mugs and smartphones, they look like anybody in the cosmopolitan francophone population of Brussels. Now they have to understand what happened in Rwanda 25 years ago, what Neretse did or did not do in his Kigali neighbourhood and in his hometown Mataba, and ultimately choose what truth is truer between the irreconcilable versions of defence and prosecution. At the same time in the neighbouring Netherlands, the International Court of Justice relies on 15 seasoned judges, to deliberate whether there is a genocide in Myanmar.

Fast-track political education

In the Neretse trial, in the absence of material evidence, the jurors face the arduous exercise of ruling on oral history. Relying only on the fallible memories of human beings, the jurors must establish if Neretse was offering shelter and protection to Tutsi civilians from relentless génocidaires or whether he was, on the contrary, actively supporting an Interahamwe killing squad that had roamed Mataba hunting Tutsis. They have to decide who is telling the truth: witnesses who have characterised Neretse as a saviour, or witnesses who said his acts or omissions had atrocious consequences.

This is the odd reality of war crimes trials held under the principle of “universal jurisdiction”. Some jurors seem too young to have been actively listening to the news when the genocide happened in 1994. And even if they did, it would be a stretch to expect them to grasp the complexities of a story that remains furiously debated among those claiming expertise on the subject. Jurors had to quickly educate themselves through the testimonies of the investigative judges and a handful of court-vetted experts who are mostly not Rwandan.

Smiles and drama

Observing these proceedings is somewhat cinematic. The old red chairs are those of a theatre. Witnesses, like supporting actors, come and go speedily. Most take a seat – still wearing their thick hooded winter coats - at the witness table after going through the same ritual: reporting to the duty police officer in front of the courtroom, being walked into court by a clerk, making their way through the public gallery, and taking their oath. At the scruffy witness desk, the court’s clerk will take their passport and sometimes, in a rather clumsy scene, help them raise their right hand as they promise to speak the truth and nothing but the truth. Then they will sit next to a well-dressed, court-appointed Kinyarwanda translator, and will submit themselves to the possible questioning of the presiding judge, her two assessors on the bench, the 12 jurors, the 8 victims’ lawyers, the prosecutor and Neretse’s two defence lawyers. Once that is done, they are given back their passport and can move to the public gallery to sit closely next to each other. From there, they will hear how the parties try to convince the jurors.

Jurors can question the witnesses too. One of them, an attentive lady with a green coffee mug, proves herself a skilled interrogator. Other jurors are more observers, or seem to be. Some write in their own notebooks as if they were eager students. Others sit back and listen. Several rest their heads on their hands, scouting the courtroom, staring at Neretse, the judges, the prosecution and the lawyers. When Neretse’s main defence counsel takes the microphone, both his eloquence and recalcitrant behaviour towards the presiding judge seem to entertain some jurors. At times it triggers laughter. The jury seems susceptible to drama too.

In sharp contrast with deluxe justice at international tribunals, this trial has an unpretentious and non-elitist air, though it remains solemn. It is hands-on and informal, as well as intense, intimate, comprehensible - and exhausting. On the eve of the verdict one thing is certain: this trial experience will have changed just as much the life of Neretse as that of each of the jurors.

THIJS BOUWKNEGT

THIJS BOUWKNEGT

Thijs Bouwknegt is a historian and former journalist. He is a Researcher at the NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies in Amsterdam, The Netherlands, and Assistant Professor at the universities of Amsterdam and Leiden. His research focuses on the history of transitional justice, particularly in Africa. Since 2006, he attended and covered all ICC (pre-) trials in The Hague, including the Gbagbo and Blé Goudé case.